Coming Soon...

In modern times, although people’s material conditions have progressed, such advancements come at the cost of increased stress: stress from work, social circles, personal relationships, society, family, etc., which have collectively pushed people into a corner. While a certain amount of stress can motivate people to improve their lot, living under high pressure for extended periods of time greatly impacts one’s physical and mental health

Body awareness and relaxation Chan

Modern people are very good at self-restraint and ignoring the messages coming from their bodies. Like an overextended balloon, we only discover that our body is too stiff and tired when the balloon finally pops. Being aware of one’s body sensations is the first step to relaxation. People are often unaware of the physical warning signs of stress, , such as clenching teeth, hunched shoulders, squinting eyes, stomachaches , heartburn, occasional migraines, and clenched fists while sleeping, etc. All these bodily phenomena indicate that we are tense and stressed.

Actually, relaxation is our natural response, since people do not like the feeling of discomfort, and the feeling after releasing the discomfort is relaxation. Being aware of the source of the discomfort and releasing it, one can gradually be able to relax. Through the practice of Chan, we can observe the stiffness and tension in ourselves one step at a time, thereupon releasing physical and mental stress layer by layer.

Mind is the key to relaxation. To relax the mind is to simply let go, and letting go of the body is relaxation. While relaxation is performed through the body, the basis for relaxation is the mind itself. The body and the mind are one, and the body's reactions actually reflect one’s state of mind. Feelings of pressure in the body arise from the reaction of the mind towards the external environment as well as the ways we appraise our self-worth.

The process of regulating physical and mental stress using Chan is actually an inner journey of self-exploration. The wisdom of Zen manifests in many ways, ranging from defusing pressure to increasing self-awareness; understanding and accepting one's own characteristics; exploring the meaning of one's own life;, and, further, transcending phenomenal appearance to appreciate and enjoy the richness of life.

Use the mind, not force, to deal with every situation.

Master Sheng Yen often described a person whose body and mind are relaxed as a "person with nothing to do.” However the "person with nothing to do" is definitely not someone who is careless and selfish, but really puts in a lot of efforts to take care of everything at the moment. After each task is completed, it will be put down without feeling any obstructions in the mind. How to relax the mind? As Master Sheng Yen said: "Don’t force the good things, and don’t reject the bad things. Everything happens for a reason, and we should peacefully accept it, deal with it, and let go of it; then, it will be easy for us to relax. "

Learning to relax through Chan practice allows us to stay stable and calm, both physically and mentally, at all times. Chan meditation is not only a method of relaxation, but also the wisdom of life. Modern people need not only health, Qigong or psychotherapy, but a set of life principles and philosophy that can be used to settle our body and life. A person who is truly physically and mentally relaxed has a clear understanding of the value of life. When doing things, they put their mind, not force, into it; just as Chan Master DaHui ZongGao said, "where it saves efforts is where it works well." When we relax well, we can save infinite energy; therefore you can get unlimited energy wherever you save effort. Furthermore, with this ability to be effortlessly present, you are able to work more efficiently, deal with things better, and allow your mind to be more at ease.

Chan Meditation allows the body and mind to stabilize and relax.

How to be peaceful and at ease? One must know to relax. Some people might be able to relax and be at ease conceptually; however, when they encounter problems, they could not be at ease, even though their brain tells them to be calm and relaxed in order to face the challenge. Relaxation is not something that you can achieve by telling yourself to do so; instead, you need to practice using methods. Chan meditation functions precisely in this way.

(Mind) Not following the external environment.

The concept and methods of Chan meditation are present to help us relax and put the body and mind at ease. The concept of Chan tells us that the body and mind are impermanent, and so are the environments. Therefore, getting better or worse are both normal phenomena. There is no way to reject or avoid it, and instead, we should face it, accept it, deal with it, and let go of it. With such a concept in mind, we will be able to temporarily calm different mental states such as sadness and uneasiness. However we still need to practice the meditation methods to maintain stability and with different encounters as well as not follow the external environment.

Reconciliation of the body and mind, being free and at ease.

When the body is relaxed, the mind and body are reconciled. There is no conflict with yourself or others, and the body does not feel burdened. You can experience that the body, mind and the environment are unified, and you are free and at ease everywhere. Being able to relax the body and mind, there will be fewer vexations; the stress and burdens are able to be alleviated, and the mind will become clearer. If you are able to practice the relaxation of the body and mind, your concentration will naturally be higher, the body’s functions will be balanced, and your mood will be calm and peaceful.

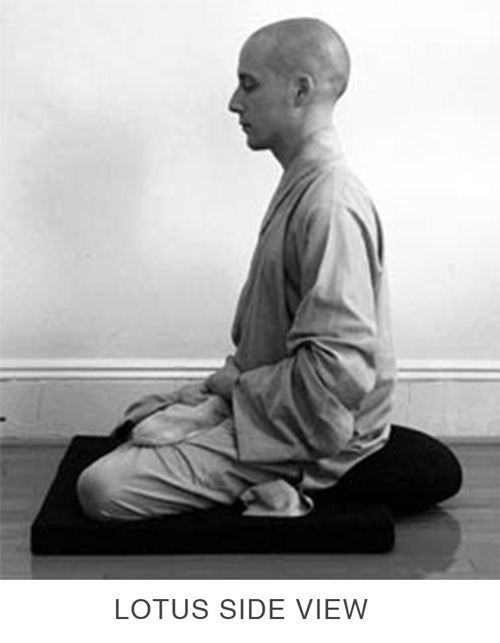

Sitting is the most effective posture for cultivating meditative samadhi.

Many different religions from India usually use sitting as the method for practice, because they maintain that sitting is the best posture for cultivating meditation samadhi. Prior to the spread of Buddhism in China, there were no established sitting methods for practicing the body and mind; rather, meditative sitting methods came mainly from India along with Buddhism.

There are three functions for sitting: the first is to create silence, which calms the body and mind; the second is to cultivate samadhi, and thus allow the thoughts to be unified; the third is to establish the basic posture for cultivating Chan meditation. Therefore, sitting is a method in many religions, not only in Buddhism, and Buddhist practitioners usually use sitting to cultivate their practice.

In the Chan School, beginners are advised to practice sitting, because the sitting posture can benefit one’s health. It is also most effective for practitioners to concentrate their mind and have fewer wandering thoughts.

The goal of Chan is to train the mind.

The real practice in Chan is not to cultivate the body but to train the mind. Not being bothered and influenced by external stimuli, such practice is called the mind unaffected by the environment. Although practicing does not necessarily require sitting meditation, the latter can certainly help people practice.

Chan methods encompass both stillness and movement. A beginner is not likely to penetrate the method using movements, and it is easier to gain deeper experience through sitting meditation. Particularly for the beginners of Chan meditation, the sitting method is concrete and simple to learn. When using sitting as a method of Chan meditation, it is easier to have a focal point to resolve vexations. Such a focus also allows for greater awareness of changes in the body and mind.

There are 3 functions of sitting meditation: first is to harmonize the body and mind; second is to attain a steady and stable mind; and third is to cultivate wisdom and compassion.

- Harmonizing body and mind: Harmonizing body and mind allows for a healthy body and mind. If a person’s body is as strong as a buffalo, but his/her mind is as fragile as a mouse, this is not a healthy state.

- Stable mind: Mind is neither entirely mental or physical, but more so encompasses both. Mind emanates functions which have no inherent forms, yet express forms through different behaviors.

- Cultivation of wisdom and compassion: If you have the experience of the unification of body and mind, as well as the unification of the self and the universe, you can unify the mind. Only when you transcend the attachment to mind and body can wisdom and compassion be cultivated. Wisdom is not knowledge or education, but is an absolute decisiveness, and an attitude of no self.

Sitting meditation can help adjust the health of the body and mind.

Chan meditation is different from sitting meditation. Sitting meditation allows the mind to enter a more stable and quiet state through sitting. Chan meditation emphasizes the cultivation of wisdom. However, even sitting meditation alone can enhance our body health. During sitting, the body is relaxed and the circulation of the blood and energy is flowing well, resulting in a very comfortable body state. . In addition, sitting and Chan meditation both help settle the mind, and allow people to reconcile their agitated mind, which in turn has great benefits to one’s mental health.

Chan meditation changes vexations to wisdom.

Most people think that meditation consists of thinking. They find themselves thinking about their problems during meditation, which allows them to gain insights and wisdom. But actually, meditation is not thinking. Thinking means to focus the mind on a specific object, but meditation requires the brain to be completely relaxed, in a state of tranquility and calmness. While sitting meditation in general appears to be similar to Chan meditation in particular, the goal and methods of sitting meditation and Chan differ.

Chan meditation itself can be divided into 2 levels: first is the level of meditation, and second is the level of Chan. Sitting meditation and Chan both function to allow the mind to enter a state of tranquility without wandering thoughts. However, sitting and meditation cannot eliminate vexations. During sitting meditation, you could feel calm and peaceful without any troubles; however, when resuming daily life and facing different people and issues, since there is still the attachment to the self, there are still vexations. In order to cultivate true wisdom in life, one must cultivate Chan. Because Chan teaching is the teaching of the mind, Chan meditation emphasizes the methods that cultivate the mind, and thus can transform vexations to wisdom. Chan meditation spans different stages, from acknowledging the self, to self-growth, to dissolve the self, and gradually to establish the right view of life. Contemplating Chan from the point of self to no self, free of vexations, one can truly be at ease without obstructions.

Excerpt from “Zuo Chan (Tso-Ch’an),” an article by Chan Master Sheng Yen

The Chinese term “zuo chan”(zazen, meditation) was in use among Buddhist practitioners even before the appearance of the Chan(Zen) School. Embedded in the term is the word “chan,” a derivative of the Indian “dhyana,” which is the yogic practice of attaining samadhi in meditation. Literally translated, “zuo chan” means “sitting chan” and has a comprehensive and specific meaning. The comprehensive meaning refers to any type of meditation practice based on the sitting posture. The specific meaning refers to the methods of practice that characterize Chan Buddhism.

CUSHIONS

If sitting on the floor, sit on a round meditation cushion or an improvised cushion, several inches thick. This is partly for comfort, but also because it is easier to maintain an erect spine if the buttocks are slightly raised. Place a larger, square mat underneath the cushion. Sit with the buttocks towards the front half of the cushion, the knees resting on the mat. If physical problems prevent sitting on a cushion, then sit on a chair.

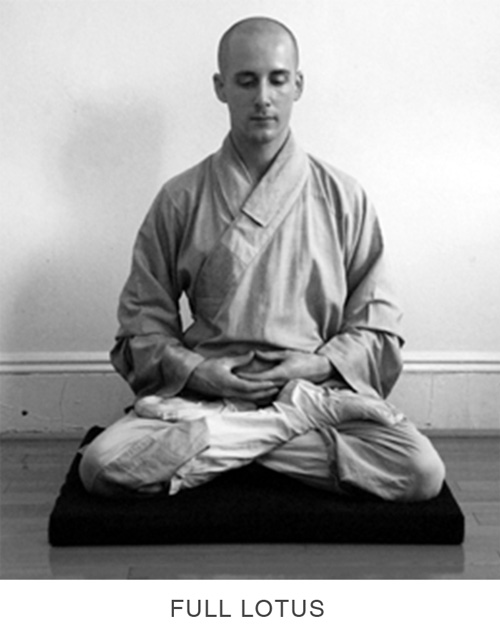

POSTURES

In sitting meditation, one should observe the seven points of the correct sitting posture. Each of these criteria has been used unchanged since ancient days. The purpose of these postures below is to stabilize the body so one can focus the mind.

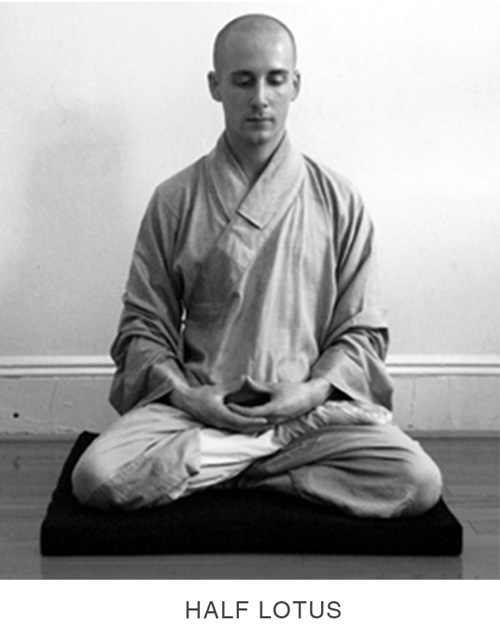

POINT ONE: THE LEGS

Sit on the floor with legs crossed either in the Full Lotus or Half Lotus position. To make the Full Lotus, put the right foot on the left thigh, then put the left foot crossed over the right leg onto the right thigh. To reverse the direction of the feet is also acceptable.To take the Half Lotus position requires that one foot be crossed over onto the thigh of the other. The other foot will be placed underneath the raised leg.

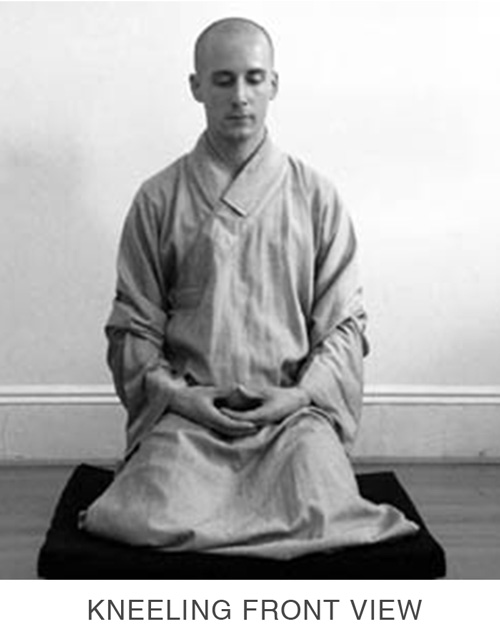

The Full or Half Lotus are the correct seated meditation postures according to the seven-point method. However, we will describe some alternative postures since for various reasons, people may not always be able to sit in the Full or Half Lotus.A position, called the Burmese position, is similar to the Half Lotus, except that one foot is crossed over onto the calf, rather than the thigh, of the other leg.

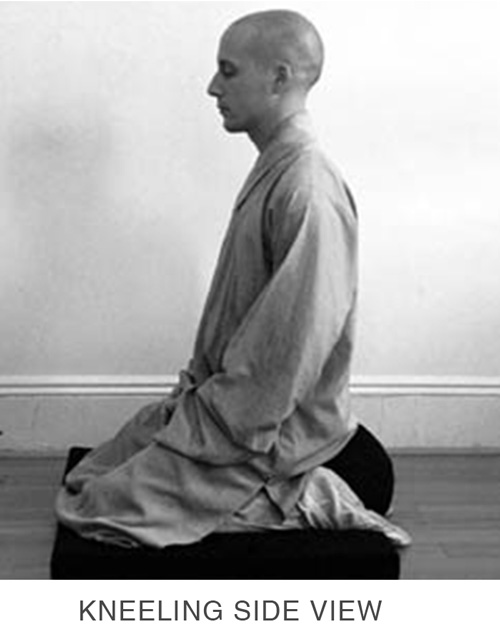

Another position consists in kneeling. In this position, kneel with the legs together. The upper part of the body can be erect from knee to head, or the buttocks can be resting on the heels.

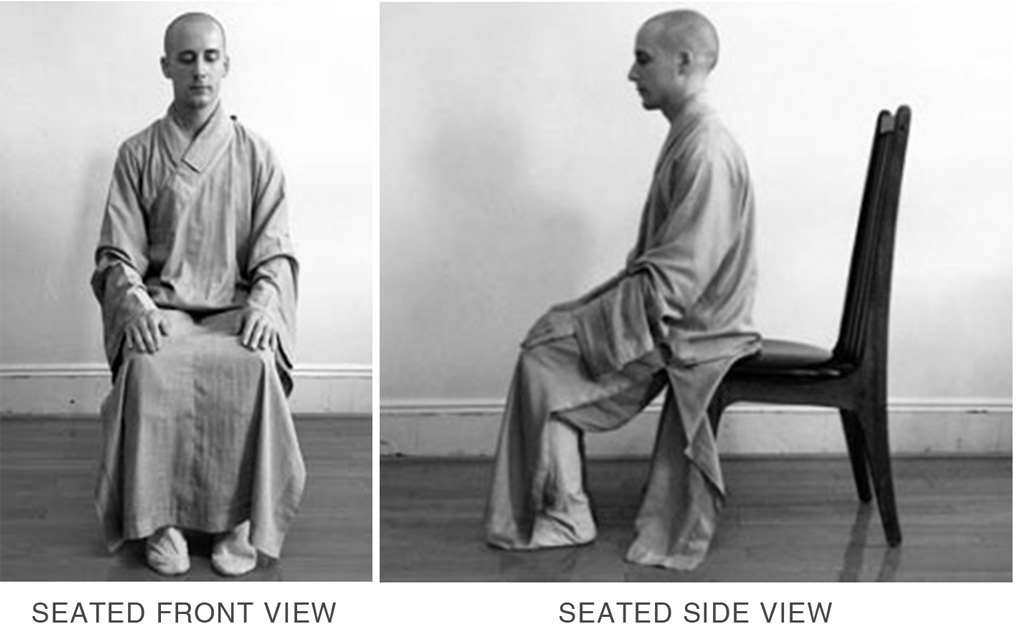

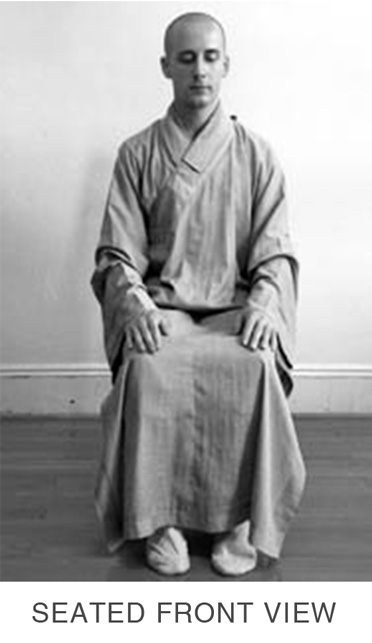

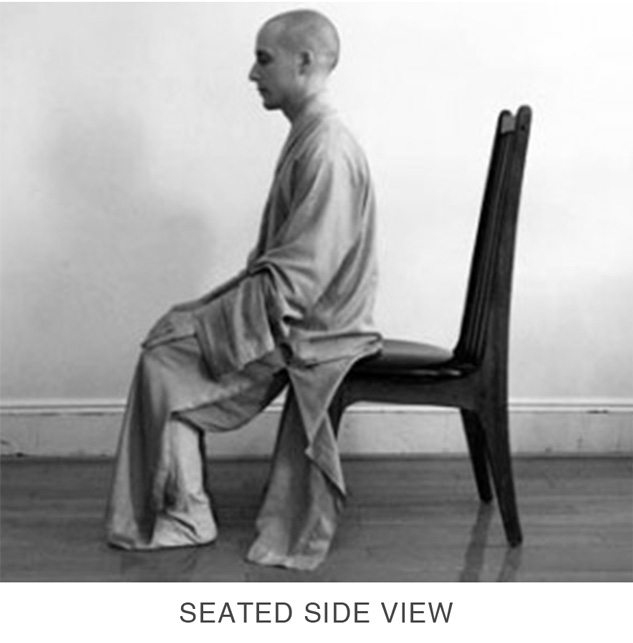

If physical problems prevent sitting in any of the above positions, then sitting on a chair is possible, but as a last resort to the above postures. The positions above are given in the preferred order, the Full Lotus being the most stable, and most conductive to good results. Sitting cross-legged is most conducive to sitting long periods with effective concentration. The position one can take depends on factors such as physical condition, health, and age. However, one should use the position in which prolonged sitting (at least twenty minutes or more) is feasible and reasonably comfortable. however, do not use a position that requires little, or the least effort, because without significant effort, no good results can be attained.

If sitting on the floor, sit on a Japanese-style zafu (round meditation cushion) or an improvised cushion, several inches thick. This is partly for comfort, but also because it is easier to maintain an erect spine if the buttocks are slightly raised. Place a larger, square pad, such as a Japanese zabuton, underneath the cushion. Sit with the buttocks towards the front half of the cushion, the knees resting on the pad.

POINT TWO: THE SPINE

The spine must be upright. This does not mean to thrust your chest forward, but rather to make sure that your lower back is erect, not just slumped. The chin must be tucked in a little bit. Both of these points together cause you to naturally maintain a very upright spine. An upright spine also means a vertical spine, leaning neither forward or backward, right or left.

POINT THREE: THE HANDS

In seated meditation, our hands form a posture called "Dharma Realm Samadhi Mudra," which translates as: the posture or gesture ("mudra") of oneness ("Samadhi") with reality ("Dharma Realm"). This hand posture helps the smooth circulation of internal energies and helps harmonize the body with the external world. The open right palm is underneath, and the open left palm rests in the right palm. The thumbs lightly touch to form a closed circle or oval. The hands are placed in front of the abdomen, and rest on the legs.

POINT FOUR: THE SHOULDERS

Relax the shoulders. Be natural. And let your arms hand loose. If you feel any tension in these areas, just relax them.

POINT FIVE: THE TONGUE

The tip of the tongue should be lightly touching the roof of the mouth just behind the front teeth. This prevents your mouth from being dry. If you have too much saliva, you can let go of this connection. If you have no saliva at all, you can apply a little bit of pressure with the tip of the tongue to the roof of the mouth.

POINT SIX: THE MOUTH

The mouth should be closed. Breath through the nose, not through the mouth.

POINT SEVEN: THE EYES

The eyes should be slightly open and gazing downward at a forty-five degree angle. Rest the eyes in that direction, but do not look at anything. Closing the eyes may cause drowsiness, or visual illusions. However, if your eyes feel very tired you can close them for a short while.

RELAXATION

Close your eyes and relax your muscles. Completely relax your eyes. It is very important that your eyelids be relaxed. There should be no tension around your eyeballs. Do not apply any force or tension anywhere. Relax your facial muscles, shoulders, and arms. Relax your abdomen and put your hands in your lap. If you feel the weight of your body, bring that sensation down to your seat. Do not think of anything. If thoughts come, recognize them for what they are and bring your attention to the inhaling and exhaling of your breath through your nostrils. Ignore everything. Just concentrate on your practice. Forget about your body and relax. Do not entertain doubts about whether what you are doing is useful.

THE BREATH

Breathe naturally, do not try to control your breathing. The breath is used as a way to focus, to concentrate the minds. In other words, we bring the two things-regulating the breathing and regulating the mind together.

The basic method of regulating the mind is to count one’s breath in a repeating cycle of ten breaths. The basic idea is that by concentration on the simple technique of counting, this leaves the mind with less opportunity for wandering thoughts. Starting with one, mentally (not vocally) count each exhalation until you reach ten, keeping the attention on the counting. After reaching ten, starting the cycle over again, starting with one. Do not count during the inhalation, but just keep the mind on the intake of air through the nose. If wandering thoughts occur while counting, just ignore them and continue counting. If wandering thoughts cause you to lose count, or go beyond ten, as soon as you become aware of it, start all over again at one.

If you have so many wandering thoughts that keeping count is difficult or impossible, you can vary the method, such as counting backwards from ten to one, or counting by twos from two to twenty. By giving yourself the additional effort, you can increase your concentration on the method, and reduce wandering thoughts.

If your wandering thoughts are minimal, and you can maintain the count without losing it, you can drop counting and just observe your breath going in and out. Keep your intention at the tip of your nose. If, without any conscious effort, your breathing naturally descends to the lower abdomen, allow your attention to follow your breathing there. Do not try to control the tempo of your breathing: just watch and follow it naturally. A less strenuous method, also conducive to a peaceful mind, is to just keep your attention on the breath going in and out of your nostrils. Again, ignore wandering thoughts. When you become aware that you have been interrupted by thoughts, just return to the method.

Although the methods of meditation given above are simple and straight-forward, it is best to practice them under the guidance of a teacher. Without a teacher, a meditator will not be able to correct beginner’s mistakes, which if uncorrected, could lead to problems or lack of useful results.

In practicing meditation, it is important that body and mind be relaxed. If one is physically or mentally tense, trying to meditate can be counter-productive. Sometimes certain feelings or phenomena arise while meditating. If you are relaxed, whatever symptoms arise are usually good. It can be pain, soreness, itchiness, warmth or coolness, these can all be beneficial. But in the context of tenseness, these same symptoms may indicate obstacles.

For example, despite being relaxed when meditating, you can sense pain in some parts of the body. Frequently, this may mean that tensions you were not aware of are benefiting from the circulation of blood and energy induced by meditation. A problem originally existing may be alleviated. On the other hand, if you are very tense while meditating and feel pain, the reason may be that the tension is causing the pain. So the same symptom of pain can indicate two different causes: an original problem getting better, or a new problem being created.

A safe and recommended approach is to initially limit sitting to half an hour, or two and a half hour segments, in as relaxed a manner as possible. This refers not only to your inner, but also your outer environ-ment. For beginners, if the mind is burdened with outside concerns, it may be better to relieve some of these burdens before sitting. For this reason, it is best to sit early in the morning, before dealing with the problems of the day. Sitting times may be increased with experience. But people who meditate for extended periods may become so engrossed in their effort that they may not recognize their tensions. This frequently exists because their minds are preoccupied with getting results. So to work hard on meditation means to just put your mind on meditation itself. If you can just do that, there is no reason for tension to arise. On the contrary, deeper relaxation, and calming of the body and mind should result.

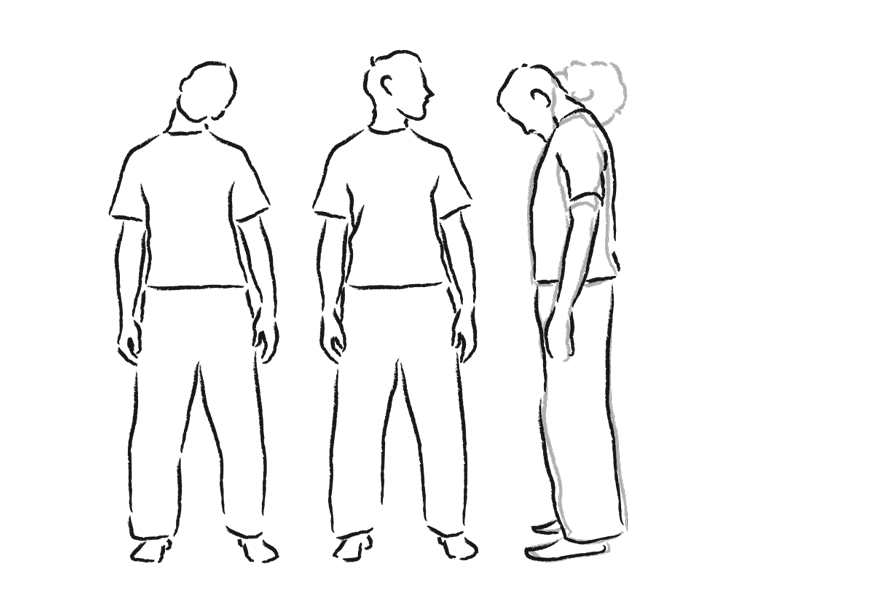

In the practice of Walking Meditation, one will walk with a concentrated mind that is not disrupted by wandering thoughts or the environment. That is to say, while you are walking, keep your mind undisturbed by thoughts or external environment.

Walking meditation is especially useful for a change of pace when engaged in prolonged sitting, such as on personal or group retreats. Periods of walking can be taken between sittings.

NATURAL WALKING

Keep your arms down and move naturally. Step forward naturally as well. Clearly be aware of the sensation of your steps. Clearly be aware of the sensation of your body moving forward. Keep your mind relaxed. Only be aware of the sensation of the movements of your body and feet.

SLOW WALKING

In slow walking, the upper body should be in the same posture as in sitting, the difference being in the position of the hands. The left palm should lightly enclose the right hand, which is a loosely form fist. The hands should be held in front of, but not touching, the abdomen. The forearms should be parallel to the ground. The attention should be on bottom of the feet as you walk very slowly, the steps being short, about the length of one’s foot. If walking in an enclosed space, walk in a clockwise direction.

Once walking starts, no need to pay attention to posture or breath. Simply just be mindful of the walking itself. Make sure your movement is smooth and steady.

FAST WALKING

Fast walking is done by walking rapidly without actually running. The main difference in posture from slow walking is that the arms are now dropped to the sides, swinging forwards and backwards, as in natural walking. Take short fast steps, keeping the attention on the feet.

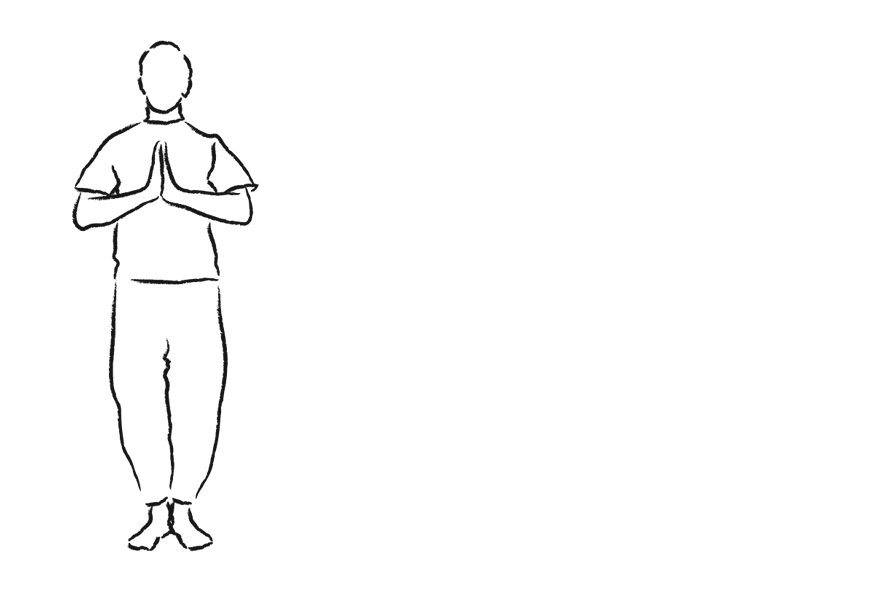

The Dharma Drum's Eight-Form Moving Meditation was developed by Master Sheng Yen of Dharma Drum Mountain as a means of allowing people living stressful and busy lifestyles to enjoy some of the benefits of Chan meditation. The system, based on many years of practice and personal experience, has incorporated the essence of Chan meditation into a series of simple physical exercises. In addition to physical exercise, practice of the Eight Forms helps you relax your body and mind, so that you can develop a healthy body and a balanced mind.

HOW TO PERFORM THE EIGHT FORMS

Dharma Drum's Eight-Form Moving Meditation is a set of easy-to-learn exercises that can be practiced almost anywhere and at anytime. This system of "meditation through motion" is beneficial to both body and mind, and once acquired through diligent practice, can be performed whether walking, standing, sitting or reclining, so that you are always mindful of being relaxed in body and mind. By practicing the Eight Forms, you will always be composed and at ease, and at every moment enjoy the bliss of meditation and the joy of the Dharma.

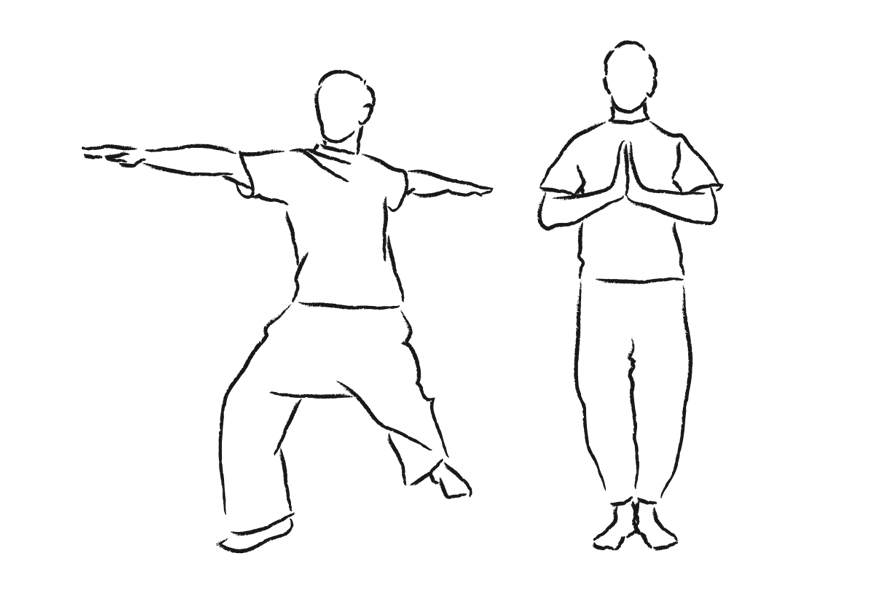

Illustrations by Jadranka Ladavac for the book Zenyoga published by Dharmaloka

STARTING POSTURE

- Join your palms in front of your chest.

- Stand with your feet shoulder width apart.

- Join your palms again at the completion of each form.

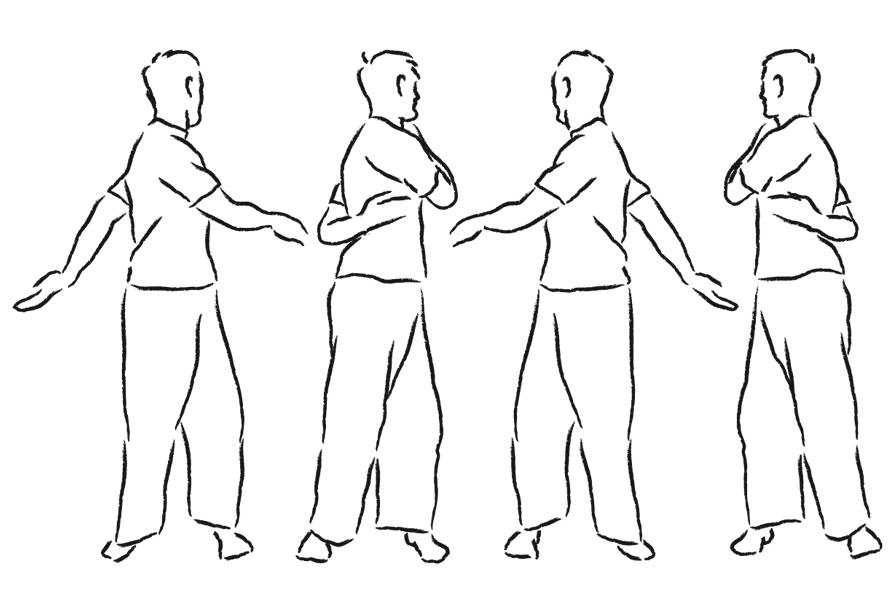

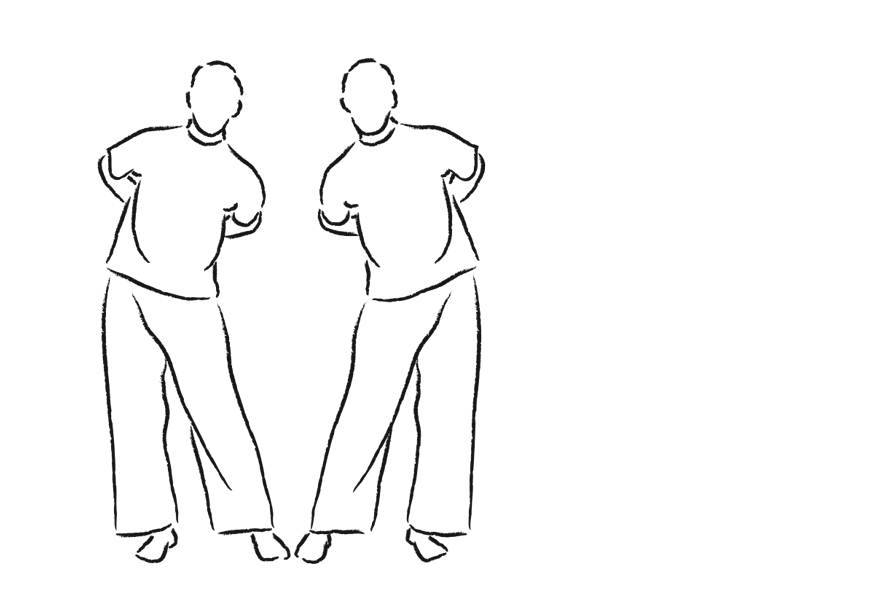

FIRST FORM: WAIST ROTATION WITH SWING ARMS

- Relax your body and stand with your feet shoulder width apart, both arms hanging naturally at your side.

- Swing your arms naturally to the left and right, turning from the waist. Your feet should remain stationary.

- As your arms swing, follow through to pat your left shoulder with your right hand and your lower back with your left hand. Reverse this action as you turn and perform repeatedly.

- Be aware of your hands patting your shoulder and back.

- Be aware of how the movement of your waist causes your arms to swing.

- Be aware of the movement of the whole body.

- Be aware of your arms and waist becoming more relaxed.

- Be aware of your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Enjoy the sensation of relaxation through your whole body.

- Join palms upon completion of this form.

SECOND FORM: NECK EXERCISE

- Relax your body and stand with your feet shoulder width apart, both arms hanging naturally at your side.

- Slowly tilt your head to the left, bringing your ear as close as possible to your left shoulder. Be aware of the right side of the neck stretching.

- Slowly tilt your head to the right, bringing your ear as close as possible to your right shoulder. Be aware of the left side of the neck stretching.

- Slowly tilt your head to the left. Feel the stretching sensation of the right side of the neck. Be aware of your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Slowly tilt your head to the right. Feel the stretching sensation of the left side of the neck. Be aware of your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Slowly turn your head towards the left as much as possible and then towards the right as much as possible. Be aware of the turning movement.

THIRD FORM: HIP ROTATION

- Relax your body and stand with your feet shoulder width apart.

- Place your hands on your waist, with the webbing between thumb and index finger facing downwards.

- Slowly rotate your hips from left to right.

- Be aware of the movement as you rotate your hips.

- Be aware of the movement of your whole body.

- Be aware of your waist becoming more relaxed.

- Be aware of your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Enjoy the sensation of relaxation through your whole body.

- Rotate hips in the opposite direction, repeating steps 3 to 8.

- Join palms upon completion of this form.

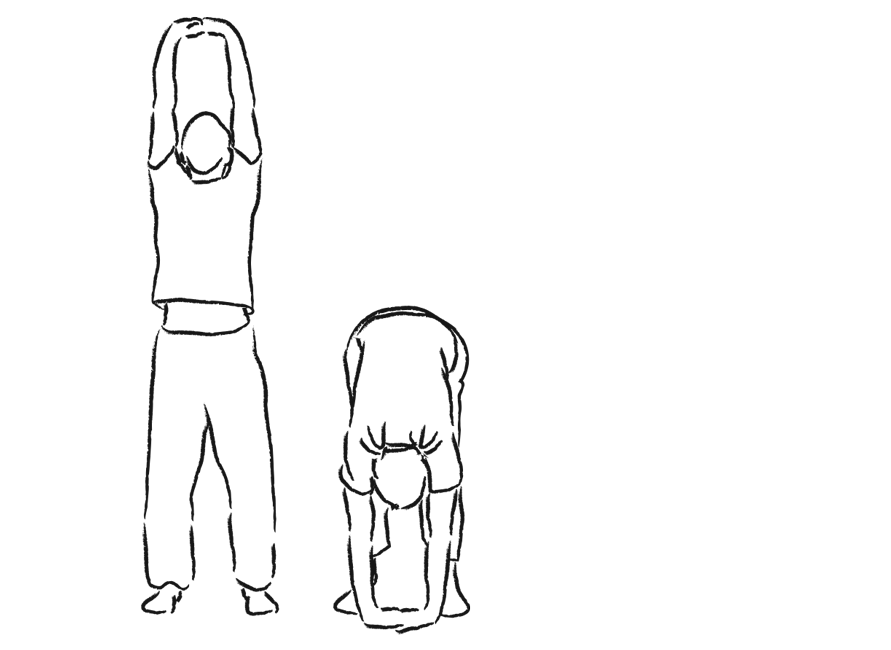

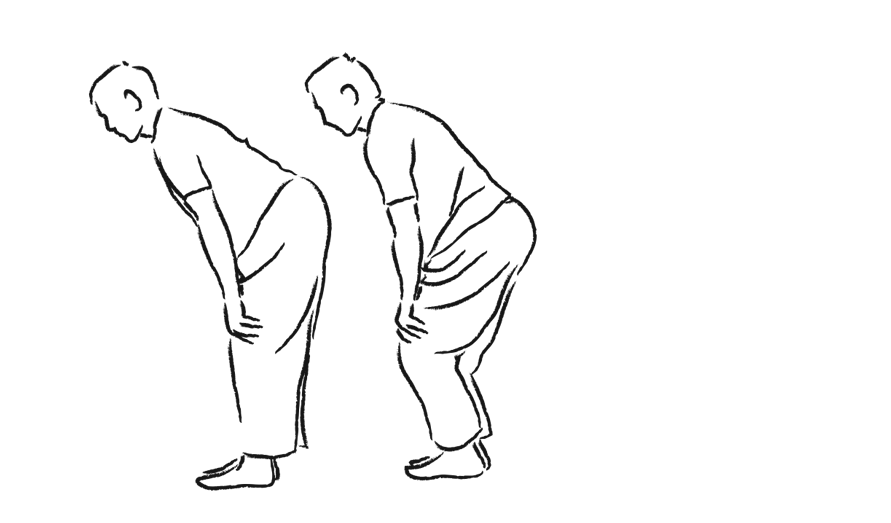

FOURTH FORM: BACK STRETCHING AND BENDING

- Relax your body and stand with your feet shoulder width apart.

- Lock your fingers and reach up slowly with both arms, palms upward, reaching as high as possible. Be aware of the sensation of stretchingas your arms reach upward.

- Slowly lower both arms. Reach down slowly and try to touch the groundwith your palms. Be aware of the sensation of stretching in your lower back and legs.

- Slowly reach up with both arms. Be aware of the sensation of stretching in both arms and through your whole body.

- Slowly reach down with both arms. Be aware of the sensation of stretching in your lower back and legs, and through your whole body.

- Slowly reach up with both arms. Be aware of your arms and then your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Slowly reach down with both arms. Be aware of your lower back and legs and then your whole body becoming more relaxed.

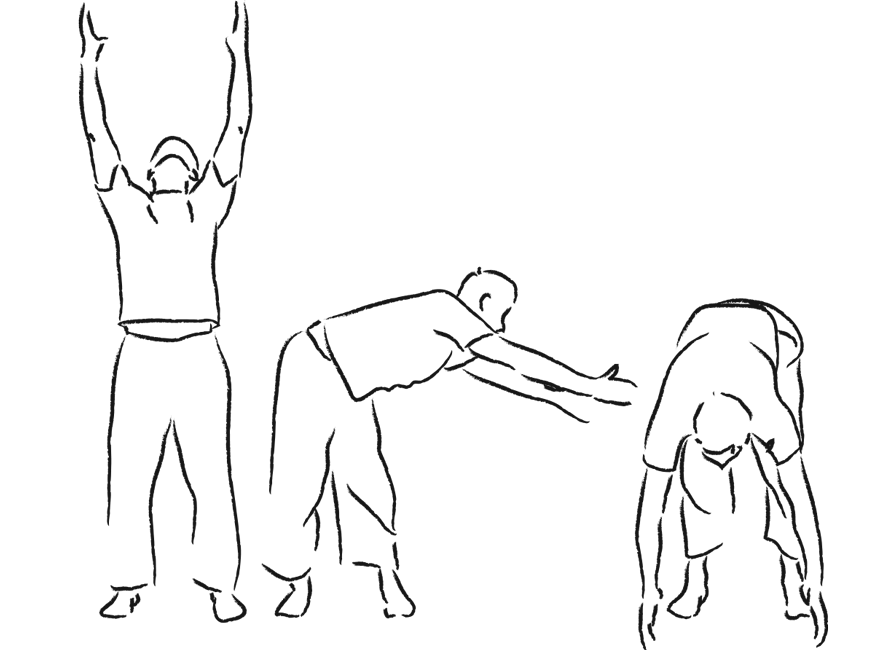

FIFTH FORM: SWING AND BEND

- Stand with your feet shoulder width apart, both arms hanging naturally at your side.

- Swing both arms forward then backward, bending your knees naturally in unison with the swinging action of your arms. Repeat continuously.

- Be aware of the swinging motion of the arms, the sliding action of the kneecaps and the movement of your whole body.

- Be aware of the sensation of relaxation in the arms and knees, and then through your whole body.

- Enjoy the feeling of relaxation in the arms and knees, and then through your whole body.

- Join palms upon completion of this form.

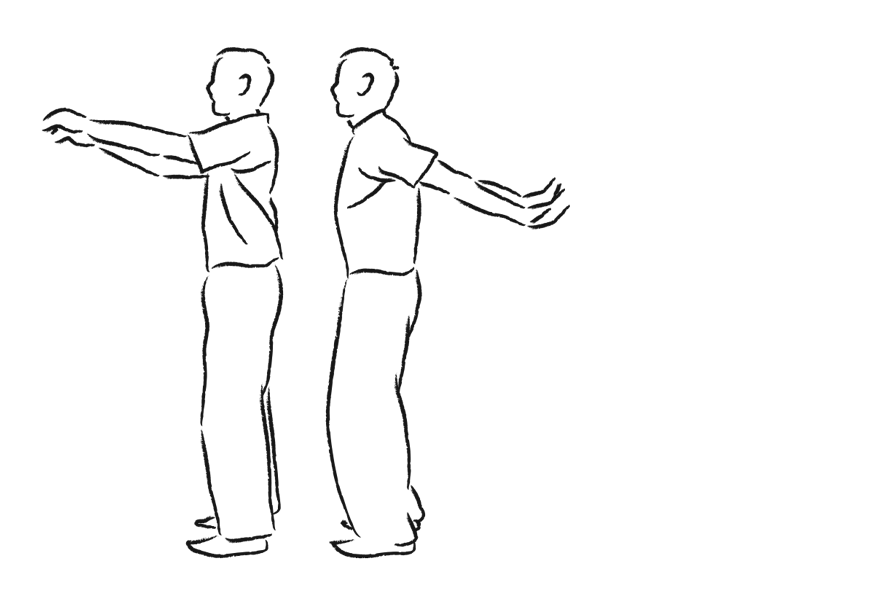

SIXTH FORM: UPPER BODY ROTATIONS

- Relax your body and stand with your feet shoulder width apart.

- Slowly raise your arms, keeping them shoulder width apart, palms facing inward as if holding a ball.

- From left to right, slowly move your upper body and your arms in a circle.

- Be aware of the rotating movement of your waist.

- Be aware of how the movement of your waist drives the movement of your arms.

- Be aware of the movement of the whole body.

- Be aware of your waist and then your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Enjoy the relaxing sensation through your whole body.

- Rotate in the opposite direction, repeating steps 4 to 9.

- Join palms upon completion of this form.

SEVENTH FORM: KNEE EXERCISE

- Relax your body and stand with your feet together.

- Bend your knees and place your hands on your knees.

- Slowly rotate your knees from left to right.

- Be aware of the rotation of your knees.

- Be aware of the movements of your whole body.

- Be aware of your knees becoming more relaxed.

- Be aware of your whole body becoming more relaxed.

- Enjoy the relaxing sensation through your whole body.

- Rotate in the opposite direction, repeating steps 4 to 8.

- Join palms upon completion of this form.

EIGHTH FORM: STRETCHING SIDEWAYS

- Relax your body and stand with your feet together.

- Slowly step forward and sideways with the left leg, bending the knee. Keep the right leg straight. Stretch your left arm forward and the right arm backward.

- Slowly return to an upright position and join your palms.

- Slowly step forward and sideways with the right leg, bending the knee. Keep the left leg straight. Stretch your right arm forward and the left arm backward.

- Repeat Step 2. Be aware of the stretching sensation of both arms.

- Repeat Step 4. Be aware of the stretching sensation in your neck, legs and waist.

- Repeat Step 2. Be aware of the stretching sensation of both arms and then the stretching sensation through your whole body.

You may click on the link below to watch a video on the eight-form moving meditation:

DDM Eight-form Moving Meditation-Standing Posture:

DDM Eight-form Moving Meditation-Sitting Posture:

The specific meaning of Tso-ch'an refers to the specific methods developed and used by the Ch'an masters to attain the state of seeing Buddha-nature. This is also referred to as seeing self-nature, wu 無, or in Japanese, kensho. The two major methods of Ch'an which have come down to us are the method of Silent Illumination 默照 and the method of the kung-an 公案/ Hua-t'ou 話頭. Each of these methods ultimately led to the founding of a major branch of Ch'an Buddhism, respectively the Ts'ao-tung 曹洞 (Soto) and the Lin-chi 臨濟 (Rinzai) schools.

In the Sung Dynasty, Ch'ang-lu Tsung-tse 長蘆宗 頤 wrote the tso-ch'an i 坐禪儀,The Manual of tso-ch'an. In it, he said that a person who has just experienced Buddha-nature should continue to practice tso-ch'an. Then it is possible to become like the dragon who gains the water, and the tiger who enters the mountains. The dragon gaining the water returns to his ancestral home, and is free to dive as deep as he wishes. The tiger entering the mountain has no opposition; he may ascend the heights and roam wherever he wills. So Ch'ang-lu is saying that practicing tso-ch'an after enlightenment enhance and deepens one's realization.

Yueh-shan Wei-yen 藥山惟儼 (745-828), an enlightened monk, was doing tso-ch'an. His master, Shih-t'ou asked him, "What are you doing tso-ch'an for? " Yueh-shan answered, "Not for anything." "That means you are sitting idly", Shih-t'ou continued. Yueh-shan said, "If this is idle sitting, then that would be for something." The master then said, "What is it that is not for anything?" The monk answered, "A thousand sages won't know."

On the one hand, we say that persons who have had realization should do tso-ch'an to enhance their enlightenment; on the other hand, we say the enlightened person sits without purpose. What is the explanation? For the practitioner whose enlightenment is not deep, practice is necessary to deepen it; for one who is deeply enlightened, practice is just part of daily life.

One day, when Ch'ao-chou was already thoroughly enlightened and actively helping others, his tso-ch' an was interrupted by a visit from a prince. He did not rise from his seat, explaining himself with a verse:

Ever since youth I have foregone meat. This body is now old. When visitors come, I have no strength to rise from the Buddha-seat.

Later, when a messenger of the prince came, Chao -chou did rise from his seat to greet the man. Chao chou's puzzled attendant asked him why he got up for the man of lesser rank. Chao-chou said, "When people of the first rank call, I receive them at my cushion. When the second rank call, I come down from my cushion. But when people of the third rank come, I go to the temple gate to greet them." These anecdotes convey the idea that the enlightened ancient masters still regarded tso-ch'an as very important.

However, if we wish to practice the Samadhi of One Act, as advocated by Hui-neng, we will remember that in the true tso-ch'an the mind does not abide in anything, hence is not limited to finding expression in sitting. For one who can continuously practice the Samadhi of One Act, the ultimate tso-ch'an is no tso-ch'an.

“Silently and serenely, forgetting all words,

clearly and vividly, it appears before you.”

不觸事而知,不對緣而照

The above line comes from the poem “Silent Illumination,” composed by Master Hongzhi Zhengjue, a 12th century lineage holder of the Caodong (Jap. Soto) school of Chan Buddhism. They describe the mind of someone who has left behind all attachment to thought and conceptualization. Doing this, they clearly know the nature of things through the direct experience of enlightenment. Master Hongzhi wrote many beautiful poems describing his deep insight. While today we can read these poems for inspiration and encouragement in our practice, they also function as guidelines for a method known as Silent Illumination. With this method, the aim is to develop and maintain relaxation, clarity and openness of mind. Ultimately, the goal is to see into the nature of the mind. One who has achieved this insight establishes a solid understanding and confidence of how to cultivate freedom and ease in dealing with all situations. Naturally, they know how to resolve their remaining vexations, and use wisdom and compassion in their daily lives.

Lost to the Chan tradition for generations, this method was neither being taught in monasteries nor was it being openly taught to lay practitioners elsewhere. Only recently was it revived by Chan Master Sheng Yen (Shifu), who has systematized its use by drawing on the writings of Chan Master Hongzhi and the teachings of the Caodong school (traceable back to the Sixth Patriarch, Bodhidharma, and ultimately to the Buddha himself). Although Silent Illumination is similar to the Zen practice of “just sitting” (Jap. Shikantaza), there are subtle differences between the two. During this retreat, you will learn how to practice Silent Illumination, starting with foundational methods to stabilize the mind, and gradually entering into what is known as the “method of no method”.

Silent Illumination – The Method of No-Method

When you first practice the Ch’an method of silent illumination, it is very simple. You just sit with the awareness that you are sitting. However, as your practice deepens, the method progresses to the point where there is no method to speak of, even as you continue in the state of Silent Illumination. The “silent” aspect is achieved when wandering thoughts no longer trouble you. Illumination, on the other hand, comes with being acutely aware of what is happening, even as your mind is silent. As your practice deepens, you no longer need to remind yourself to stay on the method. You are just constantly in the state of Silent Illumination. In this sense, Silent Illumination becomes a method of no-method.

When you first take up the practice, you still have wandering thoughts, but you are clearly aware of them. The way to deal with them is simply to keep your focus on your awareness that you are sitting. Just stay with that awareness that you are sitting. But isn’t this thought that you are sitting itself a wandering thought? Yes, it is. The difference is that this particular wandering thought, “I am sitting,” goes in one direction only, has continuity, and is constant and consistent in nature. Other wandering thoughts scatter in all sorts of directions, change all the time, and have no consistency. They vary widely in nature, content and quality. At first glance, they seem to have something to do with you, but on closer examination they are unrelated stuff thrown together like garbage.

“When used correctly, silent illumination goes consistently and continuously in the same direction, and effectively lessens and reduces other scattered thoughts. Over time, your mind becomes quieter and clearer.”

On the other hand, when used correctly, silent illumination goes consistently and continuously in the same direction, and effectively lessens and reduces other scattered thoughts. Over time, your mind becomes quieter and clearer. This is certainly not enlightenment, but at least one does not suffer as much from mental burdens, and there is stillness and clarity. The stillness is silence and the clarity is illumination. Yes, this method is still a wandering thought, but it is a wandering thought that unifies instead of scatters our mind.

We all want to make progress in our practice. For example, when you set out to journey to a faraway place on foot, every day, you know you are getting closer to your destination. When it comes to practice, it is not always clear from day to day whether you are making progress. Then there is the question of obstacles. Is it possible to make progress in your practice without encountering obstacles? When you climb a stairway, each step up is like an obstacle. You just take the steps one at a time. When you come to a landing, you can look back down and see the progress you have made. Eventually, you reach the top. In a similar way, some people may think that every time they go on another retreat, they are attaining a higher level in their practice. Some may even see each day of retreat as progress over the previous day. Then you get to the point of thinking that every sitting is progress over the previous one. But making progress in practice is not like climbing stairs.

“Is it possible to make progress in your practice without encountering obstacles? When you climb a stairway, each step up is like an obstacle. You just take the steps one at a time.”

We practice to lessen vexation and gradually illuminate the mind. But the road to that end, where the environment no longer gives rise to vexation, is marked with obstacles. When you scale a mountain, there is rarely a straight path to the top. More likely, you will encounter twists and turns, rises and dips, objects to get around and over. As you overcome these obstacles, you may get closer, but it is still not a straight walk to the summit. As practitioners, we have an ordinary being’s body and mind. We can tire mentally and physically. When this happens, it is very difficult to make progress even if you want to keep going forward, making breakthrough after breakthrough.

Therefore, if you are constantly motivated to accumulate positive experiences, the opposite—negative experiences—is likely to happen. Under these conditions, one is likely to feel frustration. This leads to negative feelings and thoughts like, “This is not for me. I’m not the kind of person who can practice well.” When you try to move forward, you meet an obstacle, or find yourself going in circles, or even going backwards. There comes a temptation to give up and leave practice to others.

“We need to remind ourselves that the purpose of practice is gradually to leave behind self-clinging and to illuminate one’s mind.”

We need to remind ourselves that the purpose of practice is gradually to leave behind self-clinging and to illuminate one’s mind. Its aim is to slow down and eventually end our struggles to satisfy our cravings and to find complete security. Craving happiness, we make sacrifices to attain it, and this sacrificing causes suffering. The quest for happiness causes our suffering, and to escape suffering we seek happiness. This cycle of happiness and suffering constitutes the ego-centered self.

As for security, we build a wall around ourselves to protect our possessions and our happiness. Over time, this wall gets thicker and thicker, and we lose touch with the self inside the wall, as well as the world outside the wall. This is egocentric. The purpose of practice is to gradually eliminate self-craving and self-protection, so that the ego, the protective wall, slowly fades away until it is eliminated.

“It is not that the self disappears, but that it has been transformed.”

The thought of having no self may seem frightening and dangerous, but in fact when you begin practicing, you need the self that is already there. Otherwise, you are either in a vegetative state or you just don’t know who you are. In the latter case, you would be a fool. So, you start practicing by relying on the vexed self. With practice, the vexed self will become a self of compassion and wisdom. It is not that the self disappears, but that it has been transformed.

One practitioner told me that as a result of practice he felt that his self was beginning to disappear, and that scared him. “Everything else can disappear, but I don’t want my self to disappear! If I disappear I won’t have a girlfriend anymore. I don’t think I want to practice anymore.” I told him that as he practiced, his mind of vexation would transform into a mind of wisdom and compassion. When that happened, he would be more capable of bringing love to others, to his family and friends. Not a possessive love, but rather a love that comes with offering yourself to others out of compassion. As one loves others in this compassionate, selfless way, what one gets back will make one’s life more fulfilling and happier.

So, looking at it this way, how do you measure progress in practice? You cannot quantify progress. It’s not like getting paid for work by the day, and every day you work, you put the money in the bank and watch your account go up and up. Progress cannot be accumulated and quantified like this. As you practice, concern about your progress is just another wandering thought, like any other wandering thought. As always, when you become aware of wandering thoughts, just return your focus to the method and they will leave of their own accord. As you eliminate wandering thoughts, you are at the same time letting go of attachment and vexation. As I said, the method itself is a wandering thought, but one that goes in the same direction and is orderly and consistent. So, it is different from the scattered thoughts that bring us suffering and vexation.

Using the method, some may sit well in one period and not be bothered by wandering thoughts. It will be a pleasant experience, and right away they will feel better. After this, they will say, “Hmmm, I really like this; I’d like to have one more pleasant sitting.” So, during the next period he or she is waiting for the pleasant experience to return. In fact, the next sitting may not be as good, or may be much worse. This person became attached to the positive experience and, as you remember, attachment is a wandering thought. As a result of anticipation, this person was not focused on the method of practice. When you attach to pleasant experiences, you are setting yourself up for disappointment.

“Yes, it is really exhausting, but you keep climbing the glass mountain until the mind that has been climbing eventually disappears.”

Think of practice as climbing a glass mountain, very slippery and very steep. To make things worse, before climbing that glass mountain, you cover yourself with body lotion, so you are very slippery as well. Now as you try to climb the glass mountain, you go a couple of steps and slip backward. Nevertheless, every time you slip, you try again. This is the attitude you should have towards practice. Every time you go forward, you may fall backward, yet you must keep climbing onto the road of practice. Yes, it is really exhausting, but you keep climbing the glass mountain until the mind that has been climbing eventually disappears. When you no longer cling to the thought of climbing the mountain, your mission has been accomplished. Have you reached the summit? No, but that is not important, because the mission has been accomplished. You may think, “If that is the case, I won’t even make the effort to climb the mountain at all, since it’s so much work.” But that is not a correct view, because before trying to climb the glass mountain you have this self-centered ego. Only through the process of climbing can you gradually eliminate self-centered ego.

Of course, climbing the glass mountain is just an analogy. In actual Ch’an practice, there are two approaches we use to dissolve the self-center. The first is the sudden approach, which is an intense, explosive approach where one keeps pounding at the self-center until it breaks apart. This approach uses a huatou (Japanese, koan), such as continuously asking yourself, “What is my original face?” The purpose of huatou practice is to give rise to a sense of doubt which grows bigger and bigger until, when it finally explodes, one realizes sudden enlightenment.

The second method is Silent Illumination, which slowly calms the mind until it is completely settled. This is a gradual method where one allows wandering thoughts and vexations to slowly dissipate. You can liken this method to a pool of very muddy water. If there is no wind or activity to disturb the pool, the mud will gradually settle to the bottom, allowing the water to become clear. Like the clearing of the pond, silent illumination seeks stillness and clarity. One keeps letting the mind-dust settle until all of it has reached the bottom. Ultimately, there is no mud, no water, and no bottom. This will be when one realizes enlightenment.

In Silent Illumination you start with being aware that you are sitting. As you focus on being aware of yourself sitting, and the body sensation itself disappears, you should still maintain the thought that you are sitting. While you maintain this thought, be clearly aware of the environment around you. Be aware that the environment is also sitting with you. After that, you even put down the thought of “I am sitting” so that there is no “I” who is sitting. There is just a clarity that you maintain, but the “I” is not there.

If there comes a moment when you ask, Where am I? Is my “self” still there?, you have left your method and are involved with wandering thoughts. Just go back to the method, being acutely aware of yourself sitting.

Silent Illumination and Shikantaza

Lecture given by Master Sheng-yen during the Dec. 1993 Ch'an retreat, edited by Linda Peer and Harry Miller, published in the Ch'an Newsletter in 1995

The Japanese term "shikantaza" literally means "just sitting." Its original Chinese name, mo-chao, means "Silent Illumination." "Silent" refers to not using any specific method of meditation and having no thoughts in your mind. "Illumination" means clarity. You are very clear about the state of your body and mind.

When the method of Silent Illumination was taken to Japan it was changed somewhat. The name given to it, "just sitting", means just paying attention to sitting or just keeping the physical posture of sitting, and this was the new emphasis. The word "silent" was removed from the name of the method and the understanding that the mind should be clear and have no thoughts was not emphasized. In Silent Illumination, "just sitting" is only the first step. While you maintain the sitting posture, you should also try to establish the "silent" state of the mind. Eventually you reach a point where the mind does not move and yet is very clear. That unmoving mind is "silent," and that clarity of mind is "illumination." This is the meaning of "silent illumination."

Faith in Mind, a poem attributed to the Third Patriarch of Ch'an, Seng-Ts'an (d. 606), begins with something like this: "The highest path is not difficult, so long as you are free of discriminations." "Discriminations" can also be translated as "choices," "selections" or "preferences." The highest path is not difficult, if you are free from choosing, selecting or preferring. You must keep the mind free from discrimination and attachment. The method in which the mind is kept free from discrimination and attachment is what is called "silence" here. But "silent" does not mean the mind is blank and cannot function. The mind is free from attachment, clear, and yet it still functions.

We also read in Faith in Mind that, "This principle is neither hurried nor slow. One thought for ten thousand years." "This principle" is the mind of wisdom, and from its perspective time does not pass quickly or slowly. When we meditate or work, we may fall into a worldly samadhi state and feel that time passes very quickly. In an ordinary state we may feel that time passes quickly or slowly. However, in the mind of wisdom there is no such thing as slow or hurried time. If we can say there is thought in the mind of wisdom, it is an endless thought which never changes. This unchanging thought is no longer thought as we usually understand it. It is the unmoving mind of wisdom.

In the Song of Samatha of Master Yung-chia Hsuan-chueh (665 - 713, also the author of the Song of Enlightenment), two Chinese terms are used which can be translated as "quiescence" and "clarity." Master Yung-chia uses them in two phrases, "quiescence and clarity," and "clarity and quiescence." They describe a person whose mind is both clear and unmoving. When an ordinary person's mind is clear and alert, it is usually also active and full of scattered thoughts. Quiescence of mind is difficult to maintain. When the mind is quiet, it usually is not clear, even in a samadhi state. But Yung-chia describes these two states, quiescence and clarity as well as clarity and quiescence, as goals.

Master Hung-chi Chen-chueh (1091-1157), who invented the term "Silent Illumination" in his poem the Song of Silent Illumination, said this

In silence, words are forgotten.

In utter clarity, things appear.

"Words are forgotten" means you experience no words, no language, no ideas, and no thought. There is no discrimination. This, in combination with the second phrase, "In utter clarity everything appears," means that although words, language and discrimination do not function, everything is still seen, heard, tasted and so on.

Someone told me that when he uses the Silent Illumination method, he eventually gets to a point where there is nothing there and he rests. That is not true Silent Illumination. In Silent Illumination, everything is there, but the mind is not moving. A person may think he or she has no thoughts because the coarser wandering thoughts are absent, but there will be fine, subtle wandering thoughts of which he or she is unaware. He or she may think there is nothing there and so stop practicing. In Chinese this is called "Being on the dark side of a mountain in a cave inhabited by ghosts." The mountain is dark, so there is nothing to see, and in the cave of ghosts, what can one accomplish?

Now I would like to explain how to use the method of shikantaza. First, your posture should be upright. Do not lean in any direction. Be clear about your posture, because if you practice shikantaza, just sitting, at the very least you should be conscientious about sitting. It is also important to remain relaxed.

Next, be aware of your body, but do not think of it as yourself. Regard your body as a car you drive. You have to handle the car well, but it is not you. If you think of your body as yourself, you will be bothered by pain, itchiness and other vexations. Just take care of the body and be aware of it. The Chinese name for this method can be translated as "just take care of sitting." You have to be mindful of your body as the driver must be mindful of the car, but the car is not the driver.

After a period of time, the body will sit naturally and cause no problems. Now you can begin to pay attention to the mind. If you were eating, your mind should be the "mind of eating," and you would pay attention to that mind. When you are sitting, your mind should be the "mind of sitting." You watch this sitting mind. Two different thoughts alternate: the mind of sitting and the mind, or thought, that watches the mind of sitting. First you watch the body sitting with little attention to the mind. When the body drops away, watch the mind. What is the mind? It is the mind of sitting! When your attention dissipates, you will lose awareness of this sitting mind and the sensations of the body will return. Then you should again watch the body sitting. Another possibility is that while you watch the mind you fall into a dull state, like "Being on the dark side of the mountain in a cave inhabited by ghosts." When you become aware of this situation, your bodily sensations return, and you should go back to watching them. Thus, these two objects of attention, the body and the mind, are also used alternately.

In the state where you watch the mind, are you aware of the external environment, such as the sounds around you? If you want to hear sound, you will, and if you do not want to hear sound, you won't. At this point, you primarily pay attention to your own mind. Although you may hear sounds, they do not create discriminations.

There are three stages in this practice. You should start at the beginning and progress to deeper levels. First, be mindful of your body. Then, be mindful of your mind, and of the two thoughts alternating in it. The third stage is enlightenment. The mind is clear and, as the poem quoted said, "In silence, words are forgotten. In utter clarity, things appear." When you first practice, you will probably be in the first or second level. If you use this method correctly you will not enter into samadhi.

This last point needs clarification. It depends on how we use the term "samadhi." In Buddhadharma, samadhi has many meanings. For instance, Sakyamuni Buddha was always in samadhi. His mind was not moving, yet he still continued to function. This is wisdom. Sakyamuni Buddha's samadhi is great samadhi and this is the same as wisdom. When I said that in the practice of Silent Illumination, you should not enter samadhi, I meant worldly samadhi where you forget about space and time and are oblivious to the environment. The deeper kind of samadhi, which is the same as wisdom, is in fact the goal of Silent Illumination.

What good is this explanation of Silent Illumination for people who are not using this method? If you are using another method of practice and you reach a point where it is impossible to continue, you can switch to Silent Illumination and watch your body and mind. For instance, if you use the method of reciting Buddha's name with counting and you can no longer count, switch to Silent Illumination. If you use the hua-t'ou method, but find that rather than generating great doubt, you are simply repeating your hua-tou and you may reach a point where you can no longer recite it. You can then switch to Silent Illumination and watch your body and mind. Eventually, you will be able to use your own method again. Silent Illumination can provide a continuum for you in this in-between state so that you do not waste time.

I was just asked whether the enlightenment that comes from Silent Illumination is sudden or gradual. Enlightenment is always instantaneous. It is the practice that is gradual. As I mentioned earlier, the third level of Silent Illumination is enlightenment. But how does one get there? As you practice, your attachments, discriminations, and wandering thoughts gradually subside. Eventually, you simply have no discriminations, but this change is instantaneous. When the change happens, you are in the state Hung-chi Cheng-chueh described as, "In silence, words are forgotten;in utter clarity, everything appears.”

After you have some experience practicing, the sentiments and vexations you ordinarily experience may not arise during practice. It does not mean that they are gone. It just means that when you practice, they do not arise. When you use Silent Illumination, this may happen, especially at the second level, but that is not enlightenment. Practice is not like trying to clear thoughts from your mind and vexations from your life as if they were dust on a mirror. You cannot wipe the dust away and make yourself enlightened. It is not like that. Whether you use the methods of the Lin-chi or Tsao-tung sects within the Ch'an tradition, once enlightened, you realize that enlightenment has nothing to do with the practice that brought you there.

So, why bother to practice? Practice is like a bridge that can lead to enlightenment, even though enlightenment has nothing to do with practice.

“Don't worry about whether or not you

become enlightened-simply pick up the huatou.”

莫管悟不悟,單提斯話頭

“Huatou” in Chinese, literally means “the origin of words,” or that which precedes words and language. This refers to the state of the mind before the arising of conceptualization or, more precisely, before the arising of a single thought. Thus, huatou is the source of all words and of all thoughts, the fundamental nature of the mind. But, it is also a method that we use to point directly at this mind while putting aside all other concerns. When we investigate huatou, we utilize questions such as: “What is my original face?” and “What is Wu?” These puzzling, seemingly illogical questions produce a deep sense of self-questioning which is called “the doubt sensation.” If you can succeed in penetrating this doubt, you will discover that which you have always had. As a result, you’ll find real peace and ease,both within yourself and together with others, generating wisdom and compassion.

Widely in use since the 12th century, huatou is a method unique to the Chan school, popularized by Chan Master Dahui Zonggao of the Linji Sect. and advocated in the last century by the great Chan Masters Xuyun (Empty Cloud) and Laiguo. In more recent times, Chan Master Sheng Yen made a unique contribution to Chan by systematizing the application of this method, making it clearly comprehensible even to the beginning practitioner. During this retreat, you will receive guidance from the teacher that will enable you to practice in a manner most suitable to your current conditions. Instruction in this method may be gentle or vigorous–depending on the style of the teacher and the causes and conditions of the student. Thus, you are encouraged to attend this retreat with no expectations and “simply pick up the huatou.”

The Huatou Method

The following are some common questions on the Huatou Method, with answers provided by Master Sheng Yen, published in the Ch'an Newsletter in 1983.

Q: What is the huatou method, and how is it related to the great doubt?

The huatou is a question that you ask yourself as a way of practice. “Hua” means words, while “tou” means head or source. When we practice on a huatou, we are trying to find out, "What is there?" before the application of any literal or symbolic description (or hua). In the beginning of the practice, there is no doubt to speak of. It is only when you are practicing this method very well that you will generate a doubt. When the practice grows to be more and more powerful, small doubt becomes a great doubt. At this point you are no longer aware of your body, the world, or of anything. There is only one thing left, and that is the question; the great doubt. When people arrive at a genuine great doubt, and if they have very sharp karmic roots, it is possible for them to get enlightened, with or without the guidance from masters. But for people with only mediocre karmic roots, they may even fall into demonic states.

The great doubt is possible only when the question of the huatou is important to them and they are seriously into the huatou. Some are not serious or earnest in seeking the answer to the question of birth and death, let alone what their original being is. Or they find their lives going on pretty well and don’t' genuinely care what they were before they were born or what they will be after death.For such peop1e, no matter how they try to ask themselves the question of a huatou, like "Who am I?" they probably will not generate a great doubt, because the question is not important enough to them. Possibly, they can get a small or medium doubt. It is said that if you have a great doubt, you can have a great explosion -- referring to the experience of enlightenment. If you only have a small doubt, you can only have a small explosion. If you don't have any doubt, you cannot have any explosion. So, before you have any explosion, you must be practicing to the extent that you essentially drop off attachment to anything-- in a manner of speaking, not wearing a single inch of silk, that is, completely naked. But, actually, even when a person is completely naked, there may still be a lot of things in his mind. One must practice until there is nothing left in his mind; one is just practicing the huatou.

Q: Does one need to use language to ask the question? Maybe words can lead to mechanical repetitions.

Definitely, you have to use language. If you do not use language to ask the question, you may be sitting there with your eyes wide open and won't be able to produce the doubt. We must have something to hold onto in our practice in order to exert our energy, and the hua (words) in huatou is that thing onto which we hold. If there is nothing to hold onto, there is no way to gather our mind together, and the doubt has no basis upon which to arise. To give an analogy, the hua is like a very long tangled cord in a basket and you don't know how long it is. You are holding onto one end of the cord. You try to get to the other end to see what there is. What do you do? You keep on pulling the thread. There is a spring in the other end. So, to get to the other end, you must continuously pull. Even if you stop for a moment, you cannot let go of your hold; otherwise, the whole thing will retract again, beyond reach. . You must exert your energy, never let go, and keep on pulling. You can never be discouraged and ask,“How come I still haven't come to the end of the thread?” You simply cannot do that. You just continue pulling and pulling and pulling, and then eventually you get to the other end of the thread, at which point you discover that there is nothing there. This may seem very foolish. In the beginning there was nothing there: you find one end of the cord and you keep on pulling until you get to the other end, and see again there is nothing there. Why bother pulling it, then? It is not foolish. The process is a method. Before you go through this process and adopt this method, your mind is confused, and your wisdom is non-existent. But after you have gone through this process, wisdom manifests.

Q: Is it possible to practice Ch'an without using any huatou, at all? After all, in ancient days, nobody had ever heard of huatou. From Bodhidharma to the sixth patriarch, even the seventh patriarch, people didn't know of any huatou. Why is it that after the Sung Dynasty using the huatou was promoted? Is it O.K. if we also do not use any huatou these days?

Ch'an master Huang Lung once said to his disciple, "If I don't give you a huatou to practice and just let you go and find your own way, probably you will exhaust yourself physically and mentally and you still will not be able to come up with anything. In that case, it will be I who have done you harm, not doing justice to your ability to practice." Since the Sung Dynasty, people have had very scattered minds. What makes things worse is that they have a lot of ideas and conceptions. Hence, it is extraordinarily difficult for these people to practice if they do not have a huatou.

Giving you a huatou to practice with (or to investigate) is like sewing your lips together with a needle and thread. You cannot open your mouth to talk, yet at the same time, a person is beating you from behind, asking you, "What is your name?" You try to yell, to talk, to give reasons, but you cannot open your mouth. Using a huatou is precisely to block, to close your mouth. Not only your mouth, but also your mind. In this manner a different condition can potentially arise.

In the Ch'an retreats that I hold, I only let some of the participants use the huatou method. And among these people only very few attain great benefit. But, nonetheless, after a person's meditation has reached a certain stage, it is important that I give him or her a huatou to practice, to see how much he or she can practice with this method. In one retreat, I told a student to use the huatou method. In the beginning, he wasn't really "investigating" the huatou, but, rather, was just reciting the huatou. After practicing for a while, he turned back to reciting again. And then he got to the stage of "asking" the huatou. But each time he asked, he answered himself. So, each question was followed by an answer. This person is no different from those who have never used huatou.

Another person was also using a huatou method. She was meditating on the cushion and suddenly she began to yell at me, "You're just talking garbage, complete garbage!" I said, “How can you say that?” She continued to accuse me of deceiving people. It seemed that she had gotten something and her mind was very confused. Then she stormed out of the meditation hall and kept asking herself the new huatou: "Am I a man or a woman?" Some time later she came back to me, as if she were about to pick a fight, telling me that, "Regardless of whether you think you are a man or a woman, I am a woman." That was an instance of genuinely investigating a hua-t'ou.

One student, after using the huatou for a couple of days, found that the huatou simply disappeared. He thought that since the huatou disappeared, he did not need to practice it anymore. But I said, no, you still have to continue practicing using this huatou. If it disappears, relax for a while, and then go back to the huatou. If this student is to come back for another retreat with me, I will still tell him to use the same huatou. The huatou is the same, except that each time I would give him a different conception and explanation as to how to practice this hua-t'ou.

There was once a Ch'an master who, when approached by anyone, would give the person the same huatou; namely, he would raise one finger. Always the same gesture. When I first read about this, I was very surprised. Is raising one finger enough? Why does this master do the same thing for every person? Different sentient beings have different karmic roots, so it would seem that always just raising one finger may not be useful. But now I understand that even though he only raised one finger, actually, that one gesture contains limitless possibilities and functions. Whether the same or many different huatous are used for different people all depends on how the master uses the huatous. Methods are dead: it is only when you use them in a living manner that they can be useful. So, you can use many different huatous, but when they are used appropriately, they are all the same. You can also use the same huatous in many different levels, and from different angles.

There are many, many huatous, some closely resembling kung-ans. A famous one is, ”Before your parents give birth to you, who are you?” Another example is: “myriads of dharmas are reduced to one;, what is this ‘one’ reduced to?”

Q: How are these not kung-ans?

Huatou is a phrase, a sentence, or a question. You want to practice on it. You want to trace the meaning of this huatou to its source. However, a kung-an is basically a complete event. You investigate into the whole incident and try to know what it is all about. An example is the story of Nan-Chuan and the cat. Two groups of monks were disputing which group owned the cat. When Nan-Chuan came back to the monastery and witnessed the dispute, he grabbed the cat and said, "Say one thing and you can save this cat." Nobody dared say anything. Nan-Chuan cut the cat into two halves. Later, an accomplished disciple Chao-Chou came back. When he heard the story, he put his shoes on his head and walked out. Nan -Chuan said," If you had been here earlier, the cat wouldn't have died." To practice on this kung-an is to ask: What is this story all about ?

In the method of direct contemplation, whatever you see or encounter, you do not apply any interpretation or judgment to it. You do not label or compare. You are just aware of what is happening in this moment, without the filters of judgments or labels.

In this method you train your mind to directly perceive what is in front of you, using just your eyes or ears. The main point is to not engage in discriminatory thought. So, there are three principles: do not label, do not describe, do not compare. Just allow whatever is in front you to be perceived as it is. That is direct contemplation.

When you do this well, you can then progress to contemplating emptiness. Contemplation in popular usage means "thinking," "reflecting." or "analyzing." However, in Buddhism, contemplating emptiness, for example, does not mean thinking about emptiness. Contemplation is just a non-conceptual way of perception, allowing the mind to abide in a certain state.

How does one go from direct contemplation to contemplating emptiness? In direct contemplation there should be nothing on your mind besides the objects you perceive. With no concepts, labels, or comparisons attached, the mind can perceive the object as it is. Though you might persist in this state for a long time, however, it is still not enlightenment, because there is an "I" perceiving and an object being perceived.

After becoming adept at this practice, your mind learns how to maintain its clarity without fixing on the object of meditation. At this point, you are beginning to contemplate emptiness. To contemplate emptiness, do not let the mind fix on the form or sound of objects; do not fix on external events or situations; and, lastly, do not fix on internal thoughts or ideas. So, internally as well as externally, do not allow the mind to rest anywhere. Many thoughts will arise within you, and you will perceive many things outside, but let the mind detach from all that. Unlike direct contemplation, where you let your mind rest on, say, a sound, at this point you just let it go. Do not allow the free flow of the mind to be caught up with your perceptions. If you see forms, do not allow them to become the contents of your mind; just let them go. Similarly, with internal thoughts and concepts--let them go. Though many things can come up, you are simply in a state of non-abiding, of letting go. So, stay with that process of experiencing, then letting go. It is a continual process of merely noticing, in which things present themselves to your field of awareness and then vanish of their own accord.