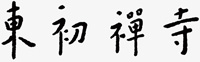

AN EXTRAORDINARY LIFE

His amusing and cordial talks make audiences feel wholly accepted and understood.

His unconventional insights bring clarity, like a ray of light penetrating the darkness.

Those who go to him seeking mystical experiences will be disappointed.

But those who observe him closely will glimpse the unhindered and unbounded wisdom of this man.

In these tumultuous times of ours, Chan Master Sheng Yen, taking the Bodhisattva Guanyin

of myriad manifestations as his model, has been seizing every chance

to lead people to inner liberation, guiding them through life's turning points

and towards a meaningful life of transcendence and giving.

Born into poverty, Master Sheng Yen lived through floods, droughts and years of war in his childhood. But in spite of these trying circumstances, he revealed his unique character at an early age.

Once, as a child, Master Sheng Yen was fortunate enough to be given a whole banana for himself. When he sank his teeth into the banana, the first he had ever tasted, he was so overwhelmed by its delicious flavor that he could not bring himself to take a second bite. Instead, he carefully saved the remainder, which was already beginning to darken, so he could take it to school the next day to let his classmates taste for themselves its wondrous flavor.

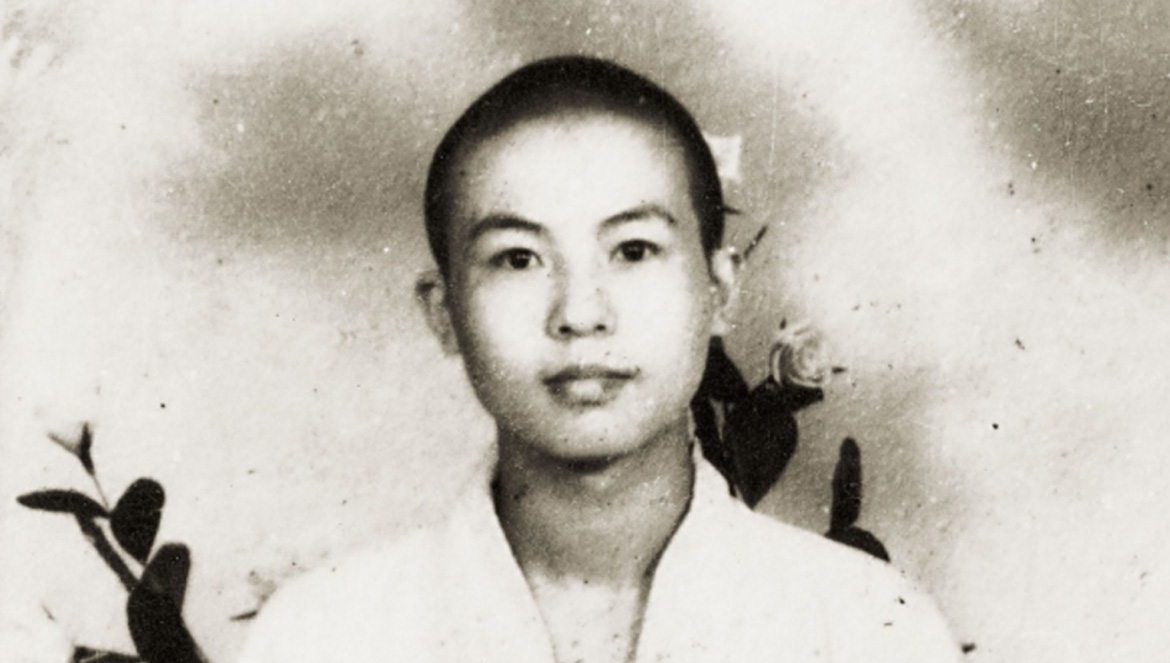

In 1943, the not-yet-thirteen-year-old Master Sheng Yen voluntarily followed a neighbor to a monastery in the Wolf Hills to become a monk. As a young novice, Master Sheng Yen was known as Changjin, and carried out the many miscellaneous duties traditionally required of monks in China's Buddhist monasteries. Although his work was exhausting, he arose before the sun every morning to prostrate himself before Guanyin five hundred times, praying to and visualizing Guanyin, a poplar twig in hand, sprinkling the cool, ambrosian dew on his head.

And how Guanyin answered his prayer. Master Sheng Yen, who at that time had only a fourth-grade education, was soon able to memorize the thick Daily Recitations for Chan Monastics and understand his masters' lectures. This brought him great surprise and joy, and he discovered that the Dharma, profound and subtle, could actually transform and liberate people. Thus he made a grand commitment: he would try his best to understand and spread the Dharma, using the Dharma to help people come out of suffering and attain happiness. To this day, in spite of the many frustrations and obstacles he has encountered over the years, this commitment has never waned. Instead, it has spurred him to develop the wisdom and will to overcome difficulties and trials.

In 1949, China was in chaos. After much deliberation, Master Sheng Yen changed his name to Zhang Caiwei and took refuge in the army. His decision was not unlike that of Hui-neng, the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism, who once joined a group of hunters to flee from danger.

Yet as a soldier, Master Sheng Yen never for a day forgot that he had been a monk; he never wavered in his conviction that he would once again take up his monastic robes and return to the path to enlightenment. In the army, the young Zhang Caiwei closely observed life in the lay world and wondered about the origins of life. Eventually, his mind was totally immersed in a great ball of doubt. Then chance brought Zhang to meet Master Lingyuan, a lineage disciple of the legendary Master Xuyun. That night, under Master Lingyuan's guidance, Zhang Caiwei experienced a powerful epiphany. A strong feeling of release swept over his whole being. Describing the experience, Master Sheng Yen says: "It was as if my life suddenly exploded out of the tin can in which I had imprisoned it."

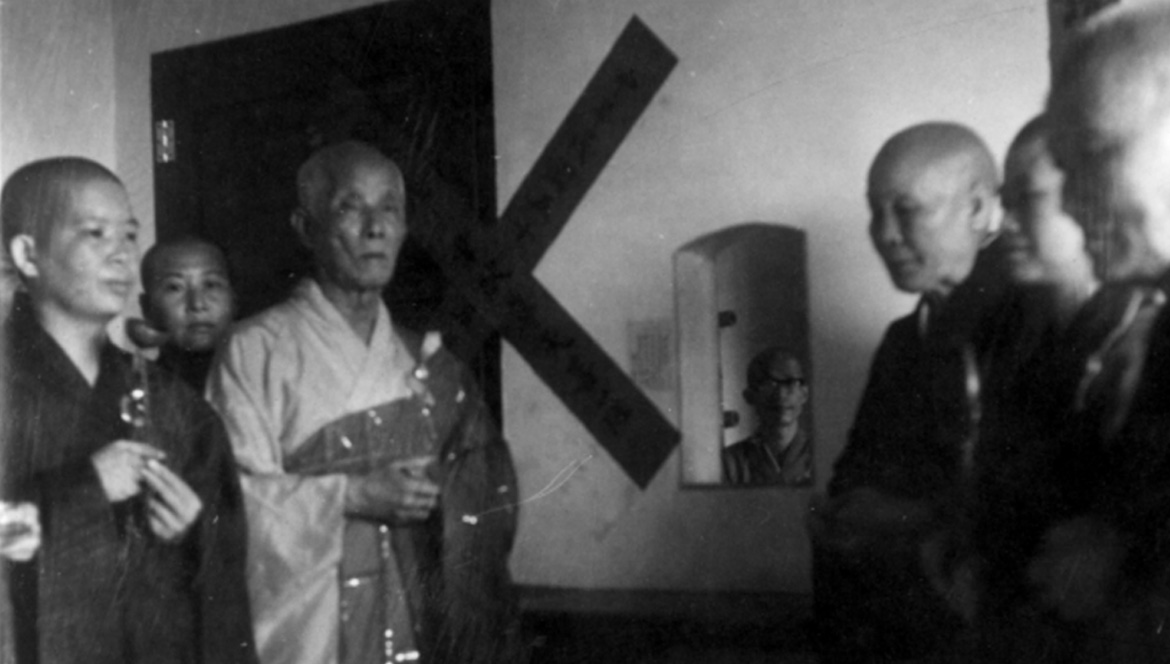

In 1960, after ten years in the service, Zhang Caiwei left the army and received tonsure again under Master Dongchu, taking the Dharma-name Sheng Yen. Not long afterwards, Master Sheng Yen went to southern Taiwan and took up a six-year solitary retreat in the mountains.

During his retreat, Master Sheng Yen placed equal emphasis on meditative practice and doctrinal learning. First he studied the precepts, then the Agama sutras. Based on this study, he wrote Essentials of the Precepts and Orthodox Chinese Buddhism, the latter of which has been translated into Vietnamese and sold more than three million copies. With regard to practice, Master Sheng Yen used the method of "no-thought" during seated meditation, and he blended martial arts and yoga to create "Chan in Motion," which later became an important element of the seven-day retreats he leads.

Having long reflected on the development of Chinese Buddhism and looking for a means to reinvigorate Chinese Buddhist culture and education, Master Sheng Yen made a firm resolve to go to Japan to study when his retreat ended. The Master's objective in becoming a scholar was to raise the status of Buddhism within Taiwanese society, and to make people understand that Buddhism, placing equal emphasis on learning and practice, is a repository of human wisdom.

In 1969, the forty-year-old Master Sheng Yen, though having only a fourth-grade education, was admitted to the master's program in Buddhist Studies at Japan's Rissho University on the strength of his published works on Buddhism. While studying in Japan, Master Sheng Yen led the life of a traditional Chinese monk. He stringently adhered to the precepts, and with natural dignity demonstrated through his actions the proper behavior for a monk in the lay world. In spite of his straitened economic circumstances, Master Sheng Yen never wavered in his resolve to study. He was guided instead by his professor's words of encouragement: "In clothing and food there is no mind for the Path, but with a mind for the Path there will always be food and clothing." Fortunately, with the timely anonymous financial support from Dr. CT Shen, Master Sheng Yen was eventually able to finish his Ph.D., becoming the first Chinese monk to do so. Master Sheng Yen's master's thesis was entitled Research on the Mahayana Approach to Calming and Contemplation, and he wrote his doctoral dissertation on the Venerable Zhixu, a Ming dynasty master. Even today, the dissertation remains unmatched for its thoroughness, detail and precision, and continues to be one of the world's few important works on Ming dynasty Buddhism.

In addition to his university studies, while in Japan Master Sheng Yen also took part in a number of retreats at Japanese monasteries. These retreats made him aware of the differences between Japanese Zen and Chinese Chan, and enabled him to incorporate the best elements of both traditions into a Chan teaching appropriate to the modern world. Causes and conditions are impossible to fathom. Master Sheng Yen arrived at the most significant turning point in his life after he completed his degreehe went to the United States to teach Chan. Speaking of those days, Master Sheng Yen says he felt like an itinerant monk pressing ahead through the wind and snow.

For the purpose of spreading the Dharma and teaching meditation, Master Sheng Yen and his students once wandered the unfamiliar streets of New York City for as long as six months.

Life was difficult, yet back then the master never felt that he was suffering. On the contrary, he says: "Those were happy times. People often say: "In spreading the Dharma, the body is forgotten." I finally had a taste of what it's like to sleep on the earth with the sky as my ceiling." Even today, those who see what the master eats and drinks are still shocked by the simplicity of his life.

And so, with this acetic spirit, Master Sheng Yen has traveled to the four corners of the Earth. These journeys have taken him to the United Kingdom, Germany, Central and South America, Eastern Europe and Russia, even to places like Czechoslovakia and Croatia, where the Dharma has rarely been heard. These extensive travels led to adjustments to his teachings, originally rich in Chinese flavor, in light of his perceptive observations and teaching experience gained along the way. Gradually, Master Sheng Yen developed a Chan teaching that transcended ethnic and cultural boundaries, one that integrated the traditional and the modern into a form that both East and West could accept.