| |

Spring 2003

Spring 2003

Volume 23, Number 2

|

Tending the Ox Tending the Ox

The great master Mazu Daoyi once asked a monk tending the fires in the

kitchen, "What are you up to?"

The monk replied, "Tending the ox."

"How does one tend the ox?" Mazu pressed.

The monk answered, "When he strays into the grass, I pull his nose

back onto the path."

"You really do know how to tend the ox!" Mazu replied.

--from Hoofprint of the Ox

by Chan Master Sheng-yen,

|

Chan Magazine is published quarterly by the Institute of

Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture, Chan

Meditation Center, 90-56 Corona Avenue, Elmhurst, New York

11373. The Magazine is a non-profit

venture; it accepts no advertising and is supported solely by contributions from members of the Chan Center and the

readership. Donations to support the Magazine and other Chan Center

activities may be sent to the

above address and will be gratefully appreciated. Your donation is tax deductible.

For information about Chan Center activities

please call (718)592-6593.

For Dharma Drum Publications please call

(718)592-0915.

Email the Center at ddmbaus@yahoo.com,

or the Magazine at chanmagazine@yahoo.com,

or visit us online at http://www.chancenter.org/

ęChan Meditation Center

Founder/Teacher: Shifu (Master) Ven. Dr. Sheng Yen

Publisher: Guo Chen Shi

Managing Editor: David Berman

Coordinator: Virginia Tan

Design and Production: David Berman

Photography: David Kabacinski

Contributing Editors: Ernie Heau, Chris Marano, Virginia Tan,

Wei Tan

Correspondants: Jeffrey Kung, Charlotte Mansfield,

Wei Tan, Tan Yee Wong, Robert Weick

Contributors: Ricky Asher, Berle Driscoll, Rebecca

Li, Mike Morical, Bruce Rickenbacker

From the Editor

As a child in the fifties and early sixties, growing up as television did, I was fondest of the science fiction -- The Twilight Zone, The Outer

Limits -- their plots, and my fascination, turned often on a simple shift of viewpoint, on an answer to the question, "Seen from a different view, an alien view, what might we look like?" Often the answer was horrific; we looked like food, or like pets, or like the infestation spoiling some greater being's picnic, but sometimes, in more thoughtful work, seen from above we simply looked foolish, childish, unable to handle our own affairs, and dangerous if left unsupervised.

We looked, in other words, much as we in the United States look now to most of the rest of the world. Today we don't need science fiction to challenge our comfortable views, we need only to pick up a European newspaper: What we see as fact -- the threat of Iraq, for example -- the rest of the world sees as clearly fiction; what we see as inevitable -- the coming war -- the rest of the world sees as quite mad. Different points of view.

Is it the flag moving, or is it the wind? Those monks had different points of view. Fortunately for them, wisdom was present with the answer, "It is the mind that moves," resolving the conflict and revealing the error; wisdom takes the larger view. Unfortunately for us, wisdom is not now present, not in sufficient quantity nor with sufficient authority to step in and resolve the conflicts and reveal the errors. All the actors are stuck in the play, each playing his own part, insisting on his own view.

What would the aliens think? Looking down at our little green planet from the mother ship; what would they think of a species willing to neglect education and health care so that they could spend hundreds of billions of their units of exchange to kill each other in order to avoid some vaguely imagined future threat? And what if they noticed that in some places millions of people were starving, while in others food was rotting, but that humans couldn't manage to deliver the food to the hungry because they were too busy arguing, in their international forums, about when and under what circumstances it was okay to go ahead and start the killing? What would be the aliens view of that?

What would be the Buddha's view?

The Editor

The Four Proper Exertions: Part One

Dharma Talk by Master Sheng Yen

This is the first of four talks on the Four Proper Exertions, given by Chan Master

Sheng Yen between October 31 and November 21, 1999, at the Chan Meditation Center, NY.

Rebecca Li translated, and transcribed the talks from tape. The final text was edited by

Ernest Heau, with assistance from Rebecca Li.

The Four Proper Exertions are really the four proper attitudes to have for those on the Buddhist path. Lacking these proper attitudes, it would be very difficult to succeed in practice, whether one is on the Hinayana path of liberation in nirvana, or the Mahayana path of liberation through helping others. The Four Proper Exertions are an integral part of the Thirty-Seven Aids to Enlightenment, which are emphasized in both the Hinayana and Mahayana traditions. Without these four proper attitudes, one can become lax in one's practice, or even give it up entirely. The Four Proper Exertions are really the four proper attitudes to have for those on the Buddhist path. Lacking these proper attitudes, it would be very difficult to succeed in practice, whether one is on the Hinayana path of liberation in nirvana, or the Mahayana path of liberation through helping others. The Four Proper Exertions are an integral part of the Thirty-Seven Aids to Enlightenment, which are emphasized in both the Hinayana and Mahayana traditions. Without these four proper attitudes, one can become lax in one's practice, or even give it up entirely.

Of the seven groups of practices that make up the Thirty-Seven Aids to Enlightenment, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness are the first, and the Four Proper Exertions are the second. This is the correct order for progressing through the Thirty-Seven Aids. We practice the Four Foundations to cultivate a calm and stable mind, and then progress to the Four Exertions to maintain diligent effort. After that we can move on to the remaining five categories to complete the practice of

liberation.

How do the Four Proper Exertions relate to the Four Foundations of Mindfulness? First, remember that the Four Foundations practice includes the Five Methods for Stilling the Mind. Thus, after one practices the Five Methods of Stilling the Mind, one is capable of calming one's mind. However, at that stage one is at most able to enter samadhi. There is no wisdom at that stage, After practicing the full course of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, wisdom can arise, and one is on the way to liberation.

As a path. Buddhism has three major disciplines: precepts, samadhi, and wisdom. But even if one practices precepts and samadhi, without wisdom there is no entry to nirvana. To seriously practice Buddhism, one should engage all three. To attain wisdom, one should practice contemplation as taught in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness.

The Wisdom of Contemplation

There are two approaches to the practice of the Four Foundations, that of the Hinayana and that of the Mahayana. In the Hinayana, the emphasis is on the wisdom of contemplation

In this regard, there are four contemplations: contemplating that the body is impure, contemplating that sensation is actually suffering, contemplating that the mind is impermanent, and contemplating that phenomena are without self.

Opposing the four contemplations are the four inverted or upside-down views. The first inverted view is attaching to the body -- we love it and think it is pure. The second inverted view is thinking of sensual pleasure as bringing happiness, rather than as bringing suffering when we lose it. As a. result we hold on to pleasure, mistaking that for happiness. Third is taking the passing thoughts of the mind as the self, and mistaking this "I" as real. Finally, there is seeing phenomena as real, and relating to things as an owner -- thinking of this or that as belonging to oneself.

Having the inverted views, we experience vexations that become obstructions to liberation. To correct these views, we practice the Four Foundations of Mindfulness to reduce vexation and make progress towards wisdom. When we begin to see that the body is really impure, we will not be so attached to it. When we can see that pleasures ultimately bring suffering, we will

not be so attached to them. When we see the mind as a collection of passing thoughts, we won't see the self as permanent. When we see that phenomena are without self, we will not be so attached to gain and loss, or be so upset when something doesn't go our way.

The Wisdom of Emptiness

In contrast to Hinayana emphasis on the wisdom of contemplation, the Mahayana emphasizes the wisdom of emptiness. This idea of realizing wisdom from experiencing emptiness comes from the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, which speaks of contemplating body, sensation, mind, and phenomena as empty. Through this contemplation, wisdom is attained.

The Hinayana approach contemplates the impurity of the body, the suffering that arises from sensation, the impermanence of the mind, and the non-self nature of phenomena; the Mahayana approach directly contemplates body, mind, sensation, and phenomena as empty. At first glance, the Mahayana approach may seem easier and more direct, but unless one diligently practices the Four Proper Exertions, it is not easy to realize the wisdom of emptiness. In any case, whether practicing the Mahayana or the Hinayana approach, one needs to practice the Four Proper Exertions to make real progress.

Comtemplating Body and Sensation

How do we directly contemplate emptiness? First, concerning the body, we see that both the nature and the form of our bodies are exactly emptiness. When we can see that, we give rise to wisdom immediately. Sensations result from interactions between our sense organs and sense objects. Without either sense organs or sense objects, there would be no sensations. We should then see that sensation does not reside inside our bodies, which only contain our sense organs. in other words, sense organs by themselves do not give rise to sensation. Neither does sensation reside outside our bodies, because outside our bodies are just the sense objects. Again, sense objects by themselves do not generate sensation. Can we

say then that sensation must be somewhere in the middle, where sense organs and sense objects meet? But that's clearly impossible. So, when we are able to see that sensation resides neither inside nor outside our bodies, nor in the middle, when we can directly perceive that sensation is empty, at that instant, we can give rise to wisdom. How do we directly contemplate emptiness? First, concerning the body, we see that both the nature and the form of our bodies are exactly emptiness. When we can see that, we give rise to wisdom immediately. Sensations result from interactions between our sense organs and sense objects. Without either sense organs or sense objects, there would be no sensations. We should then see that sensation does not reside inside our bodies, which only contain our sense organs. in other words, sense organs by themselves do not give rise to sensation. Neither does sensation reside outside our bodies, because outside our bodies are just the sense objects. Again, sense objects by themselves do not generate sensation. Can we

say then that sensation must be somewhere in the middle, where sense organs and sense objects meet? But that's clearly impossible. So, when we are able to see that sensation resides neither inside nor outside our bodies, nor in the middle, when we can directly perceive that sensation is empty, at that instant, we can give rise to wisdom.

While this may sound like tricky reasoning, we are just explaining how phenomena arise from causes and conditions. Sensations occur when sense organs and sense objects come together. Without these causes and conditions coming together, there would be no sensation, which obviously cannot exist by itself. So, if one can directly contemplate the arising of causes and conditions, and how that brings about phenomena, then one is seeing emptiness.

Contemplating Mind

Now let's consider contemplating the mind. We give names such as greed, hatred, happiness, jealousy, and suspicion to our thoughts and emotions, but these names are not the true nature of the mind itself. How could they be if the mind is constantly changing? If the mind had enduring reality, how can we be

happy now and sad later, or vice versa? Or if we say, "I love this," how can we hate "this" later? Precisely because the mind is subject to

constant change, we cannot apply any name to it and say that this is the mind. So the third contemplation is seeing that although we give names

to the mind, the names are not the mind itself.

We constantly use words to describe the mind. Sometimes we say, "This person's mind is very

good," or, "This person's mind is very scattered," as if there were a real mind there. But all the

names and adjectives are just labels, not the real mind. When we say that someone's mind is very

good, it is a very ambiguous statement because the really good mind is no mind. When one has a mind, that's a bad mind! When there is a mind, it is usually

a mind of vexation -- of greed, hatred, happiness, worry -- all minds of vexation. As we said earlier, the only good mind is no mind. If we

can really contemplate mind free from all names and labels, and perceive its actual

emptiness, we can give rise to wisdom.

Contemplating Phenomena

We come now to contemplating phenomena -- seeing that phenomena are neither good nor bad. First we should distinguish between

phenomena in the mind and phenomena in the external world. If we can see that all the names that we give to our minds are actually empty, then we

can also see that the names we give to phenomena are actually reflections of our minds. When there is no mind, how can there be good or bad in the

phenomena around us? So, the contemplation of phenomena is based on the emptiness of mind, sensation, and body that we just discussed. If body,

sensation, and mind are all empty, the phenomena have to be empty as well. When we can see the emptiness of phenomena, we can give rise to wisdom.

Does this direct approach to contemplation sound easy to practice? Instead of contemplating the impurity of the body, the suffering of

sensation, and all that, we just need to look at phenomena and say, "Oh, this is empty," and "Oh, that's

empty." Is that so? [Laughter]

In Taiwan I heard a Chan master lecture on the emptiness of phenomena. The audience seemed to

really like it. Afterwards a layperson walked up with a big, bulging red envelope full of money

offerings for the lecturer, who seemed happy to be receiving it. At this moment, another Chan

master who happened to be in the audience came up and grabbed the red envelope from the

layperson. The lecturer was startled, and said, "What are you doing? Those offerings are for me!"

The master from the audience said, "You just gave a lecture in which you said everything is empty.

So money is empty; you are empty, I am empty. What difference does it make who gets the

envelope?" The master who gave the lecture said, "No, those offerings are for me." And with that,

he tried to grab the envelope from the master from the audience.

The layperson finally said, "Let me give you each an offering." The master from the audience released the envelope to the lecturer, and told

him, "Actually, I was just trying to make a point. Of course, the offerings belong to you. But you talked about emptiness, and I am asking,

how do we really practice emptiness, how can we really see that everything is empty?"

It is difficult to see important things like money, love, and relationships as empty. Can you think of

your spouse, your boyfriend, or your girl friend as empty? One way to begin to really see things as

empty is to be diligent in practicing contemplation, In the meantime, keep reminding yourself not to

be greedy, and not to attach to things like love, relationships, and money. Remind yourself

that all things are ultimately empty. When I was in Japan, a young scholar gave an excellent lecture on

emptiness. After the presentation we all got together for lunch, and this scholar sat at the same

table with us. We told him he gave a good talk on emptiness, but that he should not eat

lunch because the food was empty anyway. The scholar said, "Well, see. When emptiness meets

emptiness, isn't that also emptiness?" We agreed. Then he said, "Well, my stomach is empty, and so is this

food. So it should be all right for this empty food to go into my empty stomach. Am I correct?" Everybody agreed, so we let him eat his lunch.

What do you think? Is this the correct way to think about emptiness? In half an hour it will be lunch, so are we going to put some empty

food into our empty stomachs? [Laughter]

The Four Proper Exertions

Now we will move to our main topic, the Four Proper Exertions. There are different names for this practice. The first and most commonly used name

is the name we are using, and it basically refers to the four proper ways to maintain diligence in the practice. The second name for the practice

is the Four Cutting-offs of the Mind. This name refers to the mind as the source of vexations, and to the need to cut off those activities of the

mind that relate to attachments. By constantly reminding ourselves that we are practicing, we can make progress in cutting of the activities of

the mind that correspond to vexation. A third name for the practice is the Four Correct Ways of Cutting Off. This name refers to the need to cut off

laziness and the idleness of the mind. The fourth name is the Four Kinds of Correct and Proper Splendidness, and it refers to the four proper methods

to encourage oneself to practice benevolence, and to stop the bad deeds of body,

speech, and mind.

As we said, without practicing the Four Proper Exertions, one may become lax and not succeed in Chan contemplation. When one becomes lax, the five obstructions

of desire, anger, sloth, restlessness, and doubt can occur. We need diligence to keep

us from falling into the pit of laziness, and succumbing to the five obstructions.

So the practice of the Four Proper Exertions is as follows:

To keep unwholesome states not yet arisen from arising,

To cease unwholesome states already arisen,

To give rise to wholesome states not yet arisen,

To continue wholesome states already arisen.

The practice of Buddhadharma really is about giving rise to wholesome states and stopping

unwholesome states. What then are wholesome states and what are the unwholesome states?

wholesome states are the ten virtues; the unwholesome states are their opposites, the ten

non-virtues. The ten virtues serve as the foundation of those on the Hinayana path of liberation, as

well as those on the Mahayana path of compassion. In fact, the ten virtues also reflect the

moral standards for people in lay life.

The Ten Virtues

The ten virtues are in three parts, corresponding to bodily actions, speech, and mind. The virtues relating to actions are no killing, no

stealing, and no sexual misconduct. The virtues relating to speech are no lying, no slandering, no gossiping, and no divisive speech. The virtues

relating to the mind are cutting off greed, cutting off hatred, and cutting off

ignorance? These ten virtues are the wholesome states that are cultivated in practicing the Pour Proper Exertions.

By Contrast, the unwholesome states are the opposite of the ten virtues: killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, slandering, gossiping, divisive

speech, greed, hatred, and ignorance. Dividing the ten virtues into three categories of bodily action, speech, mind is just a coarse definition.

To go into more detail, leaving out the body and speech, and just referring to the mind, next time we will talk about the twenty different

state of minds of unwholesome, or vexatious, states of mind, and eleven ways in which the mind can be wholesome and virtuous. People are mistaken if

they believe that so long as their body does not do unwholesome things, they are wholesome. It is really in the mind that

wholesomeness is cultivated, and only when the mind if free from vexation are we

truly wholesome.

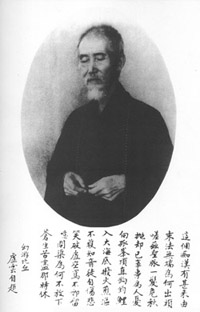

This Foolish Man

by Empty Cloud (Xuyun), the Illusory Wandering

Bhikshu

Translation by Ocean Cloud

This foolish man,

Where did he come from?

In this helpless age when the Dharma is in decay,

For what did he stick out his neck?

How lamentable -- this noble lineage,

In late autumn, hangs so precariously on a strand of hair.

Casting his own affairs aside,

He cares only for others.

He stands on the solitary peak,

Dropping a straightened hook to catch a carp.

He enters into the bottom of the great sea,

Tending the fire, boiling ephemeral bubbles.

Finding no-one who can understand his tune,

He grieves alone, in vain.

His laughter shatters the void,

And he scolds himself for being slow-witted.

Alas, you ask,

Why doesn't he just put everything down?

When the sufferings of all beings end,

Only then will he rest.

|

|

Ocean Cloud, or Sagaramegha in Sanskrit, is a group of practitioners who endeavour to bring the classics of

Chinese Buddhism to the English-speaking community in the spirit of

dana-paramita. The members are all students of Master Sheng Yen. They are: Chang Wen (David Kabacinski) from New York, Guo Shan (Jeff

Larko) from Ohio, and Guo Jue (Wei Tan) from Maryland. Hailing from various professions, they are

brought together by their enthusiasm for the Dharma and by their wish to share the exhilarating teachings of

the great masters of the Chinese traditions.

Ocean Cloud was the name of the second of 53 teachers that Suddhana, the youth in the

Avatamsaka Sutra, visited on his journey towards enlightenment. He was called Ocean Cloud because, through his contemplations, he was able to transform the vast ocean of Samsara into the ocean of highest knowledge.

Pilgrimage to China

A Special Section of Chan Magazine

"Wherever I went, I felt

like I have returned home"

Chan Master Sheng Yen

leads a pilgrimage to China

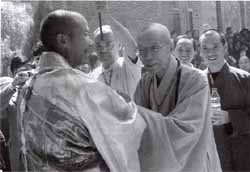

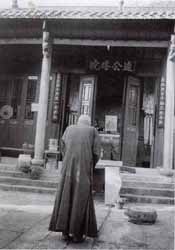

From October 3-16 of last year, Chan Master

Sheng Yen led 500 members of DDMBA, including 40 from the US, on a pilgrimage to 27 temples and monasteries in mainland China. The trip was the third such visit Shifu has led to the birthplace of Chinese Chan, the others having been in 1993, when 110 pilgrims participated, and 1996, when the group grew to 300, and like the others was arranged as a Chan retreat, 14 days of silence, walking meditation and contemplative practice. From October 3-16 of last year, Chan Master

Sheng Yen led 500 members of DDMBA, including 40 from the US, on a pilgrimage to 27 temples and monasteries in mainland China. The trip was the third such visit Shifu has led to the birthplace of Chinese Chan, the others having been in 1993, when 110 pilgrims participated, and 1996, when the group grew to 300, and like the others was arranged as a Chan retreat, 14 days of silence, walking meditation and contemplative practice.

Having converged on Hong Kong, the group set out October 3 for the Guangxiao Monastery in Guangzhou (Canton), the temple where Bodhidharma

first arrived on the Chinese mainland with the teachings that would become Chan, and where the sixth patriarch Huineng settled the famous argument, saying it was neither the flag, nor the wind, but the mind that was moving.

A caravan of 21 buses then took the group to Nanhua Monastery in Shaoguan to see the mummified remains of Huineng entombed in bronze, his image vividly

preserved for more than 1300 years. Nearby, they visited Yunmen Temple, where Chan Master Yunmen founded the sect that would bear his name.

They moved on to Hengshan in Hunan province to visit the Zhusheng, Nantai and Fuyan temples. Fuyan is where the seventh patriarch Huairang trained the great master Mazu, whose descendants founded the Linji and Weiyang sects of Chan. (Huairang sat polishing a brick, saying he was making a mirror, and likened the futility

of' that to Mazu's sitting in meditation to make a Buddha.) Fuyan is also the temple where the second patriarch of Tiantai, Huisi, lived and practiced. In Liuyang, they visited the monastery of Master Shishuang, the founder of huatou practice. The villagers there

moved the pilgrims to tears with their hospitality; they had mobilized the entire village to flatten several acres of rice field as a parking lot for the 21 buses

In Jiangxi province they visited Jingju Monastery, where Master

Qingyuan trained Master Shitou, ancestor of the Caodong, Yunmen and Fayan sects. There they also visited the temples of masters Mazu, Dongshan, Baizhang and the modern patriarch Xuyun (Empty Cloud), Shifu's own grandmaster in the Linji lineage.

The group visited the temples of the fourth patriarch Daoxin in the province of Hubei and the third patriarch Sengcan in the province of Anhui. After 10 days of bus rides on rocky roads in the inner provinces, they arrived in the modern coastal province of Fujian, where they visited the temple of Huangbo, the teacher of Linji, and the temple of Xuefeng, the ancestor of the Yunmen and Fayan sects. The pilgrimage ended in Xiamen on October 16, at the ancient temple

of Nanputuo.

One thing that repeatedly impressed many of the participants was the reception Shifu received from the monastics and students wherever he went - they wanted him to stay longer and teach them the Dharma. The monastics who greeted him, young or old, all seemed to know him, and Shifu said, "Wherever I went, I felt like I had returned home." Shifu believes, however, that by living off the mainland, he is best able to spread the Dharma throughout the rest of the world.

On November 1, at the Dharma gathering welcoming Shifu back from his trip, he gave the following impromptu Dharma talk at the Chan Meditation Center in Elmhurst, Queens, NY.

"Ultimate and Conventional

Truth Are One"

A Dharma Talk by Master Sheng Yen, November 1,

2002

The following talk was translated live by Rebecca Li, transcribed from tape by

Bruce Rickenbacker, and edited for the magazine by David Berman, with the assistance of

Rebecca Li and Wei Tan.

Have you been practicing? Yes? [laughter] Have you been practicing? Yes? [laughter]

Whether we see each other or not is not so important. What is most important is that you keep practicing. So, even if we don't see each other, you should still keep practicing.

Recently, in mid-October, from the 13th to the 16th, I was in mainland China, visiting many of the historical sites of Chan Buddhism in China. In the past, I'd only been able to read histories and gongans (koans) describing the interactions between masters and their students, and I'd always wondered, where did this story happen? In the story it says it happened in a [particular] mountain, and I'd always wondered, what does this mountain look like? I never had a chance to find out until this trip. For example, the Sixth Patriarch, Master Huineng, studied under the Fifth Patriarch in a place called Huangmei - literally it means "yellow plum." What did this place called Yellow Plum look like? Also - another example - after Huineng received Dharma transmission from the Fifth Patriarch, he had to cross a river. What was this river like? And after he crossed the river, he entered a mountain called Dayu. What was this mountain like? And then, later on he finally arrived at the Monastery of the Dharma Nature? - you may have heard the famous story of him arriving there and witnessing these two monks arguing over whether it was the flag moving or the wind moving - what was that place like? This time, I had the chance to see it all, every step of the way. It was really a fantastic opportunity.

Also, when we hear about the place where Master Huineng spoke the Platform Sutra , what does that place look like? And that place has this stream called Chao - what does that stream look like? And also, there is a monastery there called Bali Monastery, and what is that place like? Again, this time, on my trip, I got a chance to see all these places.

Also, in the Caodong tradition (in Japanese the Soto

tradition), Master Dongshan attained enlightenment while he was crossing a river - he looked into the water and saw his reflection and attained enlightenment there - and this time I had a chance to go to that river and look at my own reflection in the water.

Also, you may have heard of the story of what happened to Master Baizhang, the story of the wild fox. The story went like this:

When Master Baizhang was teaching e encountered an old man who asked him the question, "[For an adept] Is there karma?" Master Baizhang returned the question to the old man, "So is there karma?" And the old man told Master Baizhang that he had been asked this question before, that it had been five hundred lifetimes ago, and that he had responded, "No, there is no karma," and because of that [error], he had been reborn as a fox for five hundred lifetimes. The old man was

actually the fox, and was coming to Master Baizhang for the correct answer. The Master said, "Ask me again," and the old man did, and Master Baizhang responded, "An adept does not evade karma." After hearing this response from Master Baizhang, the old man said, "You have released me from the body of the fox. Please go to a cave on the mountain to bury the body."

And I'd been wondering what this cave looked like, and this time I got a chance to see it as well. And during my visit the abbot of the monastery there gave me a gift, a calligraphy of four characters, "Bu Mei Yin Guo"?

not confused about cause and effect? which are the same four words that Master Baizhang spoke in answer to the old man. As if I were also the fox coming to Master Baizhang, asking that same question.

During this visit to mainland China, I visited 27 places in six different provinces, all of them sites of origin of Chan Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty in the eighth and ninth centuries.

When I was reading these stories, I always thought of these masters as living in the mountains, on steep slopes, and when I heard of the story of Master Baizhang saying that if he didn't work the land that day, then he wouldn't eat that day, I imagined that he worked on dry land, and when I went there, I discovered that the land they cultivated is in a flat basin, and is wet, so they were working in rice paddies.

If one hasn't been to the place, it is very difficult to imagine how it looks.

There's another story about an old master working in a vegetable garden, spreading manure, and a very high government official who came in, wishing to visit this old master. He asked, "Where is Master so-and-so?" The old man replied, "What's so special about this old master? He's just like me, a regular old guy spreading manure." The minister felt that this monk was truly ignorant. How could he say that a master is just an old guy spreading manure? So he ignored the old monk, went into the monastery, and asked someone else about where Master so-and-so was, and the person in the monastery said, "That's the monk outside spreading manure."

So I was always curious what this vegetable garden looked like, and this time I got the chance to see the place, and right now that place is still a vegetable garden.

So I was always curious what this vegetable garden looked like, and this time I got the chance to see the place, and right now that place is still a vegetable garden.

Actually, I wish I could go there right now and plant vegetables; that vegetable garden is still there.

It's truly interesting, especially if you have heard and studied these stories; if you go to these places, the feeling is completely different.

There is also another story about a disciple pushing a cart filled with tools, going to work the fields. As he entered the field, the master was sitting there with his leg sticking out on the path, so the disciple said, "Master, please move your leg," and the master said, "I'm not going to move. What are you going to do?" The disciple said, "Please move your leg. I have to pass," and the master said, "I'm not going to move. What are you going to do?" and the disciple went ahead and pushed the cart over his leg, breaking the master's leg, the master yelled in pain, and the disciple laughed. This truly was a strange story. This time, I had a chance to go to that place where this whole event happened.

Right now, that place doesn't have a master like that. If such a master still exists over there, I would like to push such a cart over his leg. [Laughter.]

This definitely takes courage, Without courage, who would dare push a cart over a master's leg?

Do you understand the meaning of this story?

Student: I think it means you have to trust your own judgments, and not let somebody else make your decisions for you.

Shifu: This is a gongan, so please continue to contemplate. [Laughs] I'm not going to give it an answer. [Laughs] In fact, everybody will come up with a different answer. If you ask a hundred people, you will get a hundred different answers to

this gongan. In fact, if you work with this gongan for ten years, you will probably come up with ten different answers in the process, However, this story actually took place. It is a Chan gongan (public case).

In the place where Master Huineng approached the monastery, witnessing the two monks arguing over whether it was the wind or the flag moving, there is still a pole for a flag. There's no flag there now, but the pole was put up in memory of what took place. And when our group visited this place, there were two young monastics taking us around,

and someone asked was it the wind or the flag moving, so jokingly I pointed to the two young monastics, asking them, "Which is it, the flag

moving or the wind moving?" and these two monastics responded with a smile. And I said to everybody, "If one continues to ask the question, then it is your mind that is moving." So far, what we have been talking about, in these historical stories, these gongans...when I was visiting one of these monasteries, the people there asked that I give them a

calligraphy, that I write some words for them using brushes. Of course these words mean something, so I wrote "Er Di Rong Tong", and the meaning

of these four words is that the ultimate truth and the conventional truth are one and the same, and not different, referring to the fact that ordinary sentient beings see the conventional truth, but that enlightened beings see the ultimate truth.

Why did I give them these four characters, about the conventional and ultimate truth? It is because Chan is not separate from real life, regular daily life. Apart from the reality of daily life, there is no Chan. When I was in China, the monastic practitioners all had very big areas of land. There was one place where they had a thousand Chinese acres of land. They had planted a lot of trees, and a lot of bamboos, and they used the rest to plant vegetables and to grow food for themselves. On another mountain, the mountain where Master Baizhang was, they also have a very large piece of land, and they do the same, growing food for themselves - these monastic practitioners work in the field all day long and they meditate only at night, in the evening.

We had a chance to experience what life is like there, in the mountains - it gets dark early. When we were there, it began to get to dark around 4:30. By five o'clock, the mountains began to get blurry, because it was getting dark, so these monastic practitioners get up very early in the morning, work in the fields all day, and when it begins to get dark, they return to the

monastery - in the old days, they didn't have electricity - to practice and to listen to the master's lectures, and nowadays they live the same way, except that they have electricity now.

So, what are these two truths, the ultimate truth and the conventional truth? Well, the ultimate truth means that one is able to understand the true nature of all phenomena, which for me is the nature of emptiness, and in the Chan tradition we also call that the Buddha nature. Very often people think that when one attains enlightenment and can see the Buddha nature, it means that one can open one's eyes and see the Buddha nature, or can feel some special sensation that is called Buddha nature. [Shifu chuckles] People often have this kind of idea about Buddha nature, and these are erroneous

understandings of what Buddha nature is. [In the correct understanding of] Buddha nature, there is not one part of daily life that is not the Buddha nature; as for one's mind, all wandering thoughts are Buddha nature. The difference [between

ultimate and conventional truth] is that [in ultimate truth] there is no attachment whatsoever to these wandering thoughts.

When wandering thoughts arise in one's mind and there's no attachment to these wandering thoughts, that is being one with the Buddha nature; when wandering thoughts arise and there is attachment, that is vexation, so Buddha nature and vexation are not different. After enlightenment, one experiences

ultimate truth; before enlightenment, one experiences conventional truth. So you can see that these are not two things, but one.

When wandering thoughts arise in one's mind and there's no attachment to these wandering thoughts, that is being one with the Buddha nature; when wandering thoughts arise and there is attachment, that is vexation, so Buddha nature and vexation are not different. After enlightenment, one experiences

ultimate truth; before enlightenment, one experiences conventional truth. So you can see that these are not two things, but one.

Therefore, since the old times in the Chan tradition, practice has not been separated from daily life. The monastic practitioners we saw in China, spending a lot of time working in the

fields - I used to think they worked on the slope of a mountainside, but they actually work in a flat field, but anyway - they spend a lot of time working in the field and only part of the day meditating. What it means is that practice and daily life are not two different things. They should not be seen as separate, although a lot of people seem to think that practice only means sitting meditation. After all, we hear that at Chan retreats you do a lot of meditation. But sitting meditation is only a part of one's life, not all of it, and practice is not only doing sitting meditation. I asked one of the monastics in China, "How much time do you spend doing sitting meditation a day?" And this practitioner said five to ten periods of sitting meditation per day, and I said, "Wow, that's a lot of time for sitting meditation. You must be enlightened, spending so much time in sitting meditation." The monastic responded, "That's not the case at all. I'm just spending the time training my legs [laughter], sitting here all this time."

Let me tell you this: In the monasteries that I visited, the practitioners that spend the most time in sitting meditation are the old monastics that can no longer work in the fields. That's why they spend a lot of time in sitting meditation.

At one monastery, I met a practitioner in his eighties, who spent a lot of time doing sitting meditation, because he couldn't work in the fields, and when he saw me, he was really happy to see me, and he told me that he and a younger monk had gone to a mountain called Putou and been to a cave called Taoyingdong, and that he had seen the image of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara on the wall of

the cave, and they had taken a picture of it, and he was very happy about that, and he wanted to give me the picture as a gift because he was so proud to have seen the manifestation of the bodhisattva. And when he told me the story, I was a little surprised, thinking, "Wow! You spend such a long time - now you're in your eighties - practicing all your life, and you think the greatest thing that happened from your practice as seeing the image of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara? but nevertheless, I accepted the gift and thanked him.

Why a pity?

Why do you think I thought it was a pity? It is because he was mistaking the conventional truth for the ultimate truth.

The fact that he saw the manifestation of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara was a good thing. However, it was still an illusion, and he was mistaking this illusion for ultimate truth. The group that traveled with me, that took this pilgrimage to China, had five hundred people. We visited a monastery where a lot of people saw an image of Avalokitesvara in the sky, and somebody took a picture it. I didn't see it; I wasn't paying attention. But a lot of people saw it, and those that did were very excited about the whole experience. So at the end of the tour, when everybody reported about their experiences, quite a few of them said that had been the most important event that happened during the tour: "Wow! I saw the image of the bodhisattva in the sky!" And Guo Yuan Fa Shi said, "That was an illusion that you saw. What's so special about it? The main purpose of this tour was to see where our masters and patriarchs practiced and taught the Dharma and also, through visiting these places, to understand their inner experiences, not to see illusions in the sky." After hearing this response from Guo Yuan Fa Shi, this participant was kind of disappointed,

because he thought it was such a great thing that had happened. Actually, there's no need to scold these people for getting so excited about seeing the image of the bodhisattva, for they actually saw the image, and it really happened. However, there's also no need for people to get too excited about what they saw. The fact that they saw the image means that these individuals had virtuous roots in the practice. But the important thing is to understand that ultimate truth and conventional truth are one, and not to think that they are separate. And where is the ultimate truth? Ultimate truth is in the conventional truth.

Ultimate truth means that in one's daily life one does not give rise to vexations. One does not attach to things; one does not cause suffering to oneself, and one does not cause suffering to others. If one can follow this in one's daily life, then one is in accord with the ultimate truth, and the ultimate truth is one with the conventional truth. This is what is meant by practice in daily life, and this is the function of Chan practice in one's daily life, and so, one should not be looking for the ultimate truth apart from the conventional truth. Ultimate truth means that in one's daily life one does not give rise to vexations. One does not attach to things; one does not cause suffering to oneself, and one does not cause suffering to others. If one can follow this in one's daily life, then one is in accord with the ultimate truth, and the ultimate truth is one with the conventional truth. This is what is meant by practice in daily life, and this is the function of Chan practice in one's daily life, and so, one should not be looking for the ultimate truth apart from the conventional truth.

I've finished my talk here, and I'm supposed to leave in ten minutes, so I've thought that in the remaining time, if you have any

questions - in response to what I've just talked about, for example, you can raise the questions here.

Student: What's the state of these monasteries now? Are there lots of practitioners there? Are they healthy and vibrant?

Shifu: Since 1987, I've been to mainland China seven times. In general, the situation of monasteries in the north tends to be worse than those in the south; those in the south tend to be in better shape. The main thing is, after the Communist revolution in 1949, there was a period of about thirty years during which no one entered monastic life at all. Therefore, monastic practitioners of my age or older are very rare nowadays. Most practitioners are in their thirties. In a lot of monasteries the abbots are in their forties. Even those older than forty are rather rare. There are older people, even of my age, in the monasteries, but they didn't become monastics when they were very young like I did. They entered monastic life when they were much older. They are very diligent, but unfortunately it is very difficult to find a teacher there. They've been

The Past

Shifu Returns Buddha's Head to Body

On January 9, 2003, the New York Times reported that Chan Master

Sheng Yen, president and spiritual leader of Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association, had arranged the return of the head of Akshobhya Buddha to its original torso at the Four Gate Pagoda in Shandong Province, People's Republic of China. The massive head had been stolen in 1997, and had only recently re-surfaced when disciples of Master

Sheng Yen had donated it for the future Museum of Buddhist History and Culture at the Dharma Drum Mountain site in Taiwan. On January 9, 2003, the New York Times reported that Chan Master

Sheng Yen, president and spiritual leader of Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association, had arranged the return of the head of Akshobhya Buddha to its original torso at the Four Gate Pagoda in Shandong Province, People's Republic of China. The massive head had been stolen in 1997, and had only recently re-surfaced when disciples of Master

Sheng Yen had donated it for the future Museum of Buddhist History and Culture at the Dharma Drum Mountain site in Taiwan.

Master Sheng Yen had noticed the sculpture's damaged neck and had immediately contacted Lin Bao Yao at the Taipei National University of Arts, who identified it as being from Shandong during the Sui dynasty (581-618). Experts in Shandong then confirmed that it was indeed the missing Akshobhya Buddha from Four Gate Pagoda.

On December 17, in a ceremony that made the front page on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, the Buddha head was returned to its torso. Master

Sheng Yen accompanied it on its plane trip from Taipei, and then its bus ride to Shandong, (turning down the offer of a limousine), and took the opportunity to also visit the National Religion Bureau in Beijing, where he suggested that the Four Gate Pagoda, largely a tourist site in recent years, should once again become a religious shrine. Asked about the difficult relationship between China and Taiwan, he said that both governments had been supportive of the transfer, and expressed joy that, as a religious leader, he had been able to contribute to dialogue between the two sides.

It is unknown how the stolen artifact made its way to Master

Sheng Yen, although authorities speculate that it may have gone from China to Japan to the art markets of Europe before being purchased by a group of businessmen in Taiwan. Prices can vary greatly, but Sui dynasty artifacts in good condition are quite rare, and the value of this one has been estimated as high as $1.5 million.

Dr. Les Cole to Head DDRC

On Sunday, December 29, Master

Sheng Yen announced the appointment of Dr. Les Cole, of Atlanta, Georgia, as executive director of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center (DDRC) in Pine Bush, New York. Dr. Cole, a Christian minister and psychotherapist, has been the executive director of The Center for Children and Young Adults in Marietta, Georgia, which operates shelters for abused and neglected children and youth. On Sunday, December 29, Master

Sheng Yen announced the appointment of Dr. Les Cole, of Atlanta, Georgia, as executive director of the Dharma Drum Retreat Center (DDRC) in Pine Bush, New York. Dr. Cole, a Christian minister and psychotherapist, has been the executive director of The Center for Children and Young Adults in Marietta, Georgia, which operates shelters for abused and neglected children and youth.

Dr. Cole is already well known to many Chan Center members as the director of the Chan Summer Camp at DDRC, during which he led workshops designed to improve communication and understanding between parents and their teenage children, sessions that were very well received.

In his introduction of Dr. Cole, Master Sheng Yen described his responsibilities as including developing the DDRC and its programming, setting up an infrastructure for its operations, "marketing" Shifu and Guo Yuan Fa Shi to the western public, and coordinating construction, legal affairs and public relations at the center. In a characteristic understatement, Shifu referred to the new job as "simple, but not easy.

Dr. Cole then spoke briefly, asking for everyone's help in making the retreat center a place that can offer the medicine of Chan to help heal the many suffering beings in the world.

2002 DDMBA Convention

The 6th North American Annual Convention of DDMBA was held at the Dharma Drum Retreat Center in Pine Bush, NY, from October 25-27. More than 100 members attended from 15 states and 19 chapters, including those from Vancouver and Toronto, Canada.

Master Sheng Yen opened the convention with an address in which he reaffirmed the mission of DDMBA, that being the promotion of Chinese Chan Buddhism throughout the world. He said that while Tibetan and Theravada Buddhism were well known, Chinese Chan still needed lots of hard work to make an impression in the world. This is the challenge that we all face as DDMBA members.

Shifu went on to explain that the main purpose of his recent pilgrimage trip to China was to give DDMBA members the opportunity to witness the complexity, vastness and profundity of Chinese Chan. Unfortunately, the Chan school has been in decline for six centuries, and without education, it can never revive itself. This is why the programs of DDMBA place so much emphasis on Buddhist education.

On the second day of the convention Shifu further refined his message by

emphasizing that all DDMBA activities should contain two main purposes -- care and education. We care for both ourselves and others; we educate ourselves by learning through our activities and from other members.

Recently, DDMBA has started a new campaign: "One teacher, one tradition, one mind and one vow." The one teacher is Shakyamuni Buddha, the one tradition is Chinese Chan, the one mind is a mind of compassion and wisdom and the one vow is to uplift the education of Chinese Chan.

The convention also included sharing experiences and photographs of the recent pilgrimage trip to China, exhibits and workshops by individual chapters, a casual night of entertainment, and the appointment of new chapter presidents.

Marriage of Kevin Hsieh and Wendy Wong

On Tuesday, November 26, Kevin Hsieh and Wendy Wang tied the knot at the Chan Meditation Center. Kevin and his mother, Mrs. Kao Liu-chih are long-time members and volunteers of the center. For many years Kevin worked as the center's official photographer and computer liaison.

Kevin wanted a simple Buddhist wedding at the center to be officiated by Master

Sheng Yen. With less than two weeks' notice the date was set to fit into Shifu's busy schedule and arrangements were quickly made. Mrs. Kao hurried back from Taiwan, where she had been visiting.

Closed to a hundred guests, mostly center members, attended this happy occasion. The Chan hall was decorated festively with red ribbons, lanterns and a runner for the bridal party. Shifu offered a short talk to the couple and bestowed blessings on them, and a simple reception followed with food prepared by volunteers.

May Kevin and Wendy be blessed with good health and happiness!

Chanting and Chan Retreat

The Chan Meditation Center inaugurated its first Chanting and Chan Retreat at the Dharma Drum Retreat Center September 27-29. The two-day retreat, sponsored by the Monday night chanting group, which has been meeting for chanting practice for the last six years, was attended by forty participants, mostly regulars of the group. Guo Xiang Fa Shi supervised the retreat and Guo Chen Shi led the chanting.

This unique retreat combined chanting and Chan. Each chanting period consisted of recitation of Amitabha Buddha's name while walking and sitting, followed by a shorter period of sitting meditation, using the method of silently chanting the Buddha's name. The format was similar to that of a regular Chan retreat, with participants remaining silent throughout the retreat and performing daily work assignments. In addition, everyone was encouraged to perform 300 prostrations each day.

Guo Yuan Fa Shi gave short talks, explaining that the practice of chanting, which already existed during Shakyamuni Buddha's time, could lead to the unification of body, mind and environment. He encouraged participants to make good use of the two short days in order to derive the utmost benefit.

Winter Huatou Retreat

From December 26, 2002-January 5, 2003, Master Sheng Yen held his 100th retreat in the United States. Under a mantle of pristine snow, 57 participants assembling from all over the world-England, Italy, Israel, Poland, Finland, Croatia, Singapore, Taiwan, Canada and all parts of the U.S.-gathered at the Dharma Drum Retreat Center to diligently practice the huatou method under the watchful guidance of Master

Sheng Yen: "In the Chan tradition, the huatou is used to shatter one's confusions in order to attain enlightenment. These confusions are the manifestations of all the delusions ordinary sentient beings have. Delusions come from attachments, wandering thoughts and vexations. Therefore, in using the huatou method, one wields the huatou like a diamond sword to shatter these delusions, vexations, wandering thoughts and attachments." (A huatou is an unanswerable question-"Who am I?" and "Who is it dragging this corpse around?" are two famous ones-that one asks oneself repeatedly as a method of meditation. -The editor.)

Back

|

|