Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 119, November 1996

Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 119, November 1996

The Ten Ox Herding Pictures

A talk delivered by Master Sheng-yen on 10/22/92 and edited by Linda Peer and Harry Miller. (For further information on this subject, see Ox Herding at Morgan's Bay by Master Sheng-yen) Drawings by Nora

Ling-yun Shih.

The Ten Ox Herding Pictures are metaphors for the process and progress of Ch'an practice. When China was an agricultural society, people depended on oxen and buffalo to work their fields. These animals were important, powerful and part of human life, so the analogy of ox herding was meaningful to Buddhists of the time.

An early incidence of ox herding as a metaphor for practice can be found in a story from the T'ang Dynasty (618-906). A monk was working in the monastery kitchen when his master came in and asked what he was doing. He replied, "Nothing much, just herding the ox."

The Master asked, "How are you herding it?"

The monk replied, "Every time the ox wanders off to eat grass when he should be working, I rein him in and put him back to work."

This story became a kung-an in which the ox represents the mind, which the ox herder must train. In Ch'an practice, the emphasis is on mental, not physical, practice. If the mind is not pure, there can be no purity in body and speech.

In the Lotus Sutra the white ox is a metaphor for transcendence of the cycle of birth and death, or samsara. Anyone who sees the white ox sees the great vehicle (of Mahayana Buddhism) which can be taken to Buddhahood.

Many versions of the ox herding pictures were created during the Sung Dynasty (960-1279). They were often accompanied by poetry. The most famous is attributed to K'uo-an Shih-yuan, a twelfth century Ch'an master of the Lin-chi school. All versions illustrate the process and levels of Ch'an practice, as well as the recognition of Buddha-nature, our original nature.

Do you believe that you have this ox, this Buddha-nature, within yourself? If you have no faith in the existence of Buddha-nature, or in the possibility of experiencing your intrinsic self then ox herding is irrelevant. If there is no ox to herd, there can be no ox herding, no progression. This is true for people who have no interest in discovering their intrinsic nature, as well as for those who once held the ox and let it go.

The first picture is "Looking for the Ox." It shows a beginning practitioner who has heard the teachings of the Buddha and believes we each have Buddha-nature and the ability to attain liberation. However, he has no personal experience of Buddha-nature and must use methods of practice, such as meditation and prostration, to discover the original

self.

. .

The practitioner discovers ox tracks in the second picture. His mind has begun to calm and he has a sense of something, but he sees that the ox is not easy to find. Searching for Buddha-nature is like looking for a mountain through a thick layer of clouds. Others say it is there, but you are uncertain of what you see. Is it a cloud or a mountain? The beginning practitioner has only seen tracks. Do they belong to the ox? At this point you are attracted to practice, and practice impels you to search. Practice enhances your faith. This is seeing the traces of the ox.

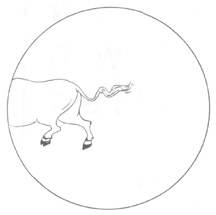

In the third picture the practitioner sees the ox's tail. Earlier, the sight of tracks gave him the faith to practice diligently and now suddenly he sees an animal. This is also described as seeing the face of pure mind, or the momentary disappearance of self-centeredness. This picture is sometimes described as seeing one's intrinsic nature, but it is only a glimpse of something -- only the tail of the ox.

The practitioner catches the ox and tries to control it with a rope in "Getting the Whole Ox," the fourth picture. He perceives his own Buddha-nature, but still experiences vexations caused by greed, anger, dislike and resentment. The mind produces innumerable vexations in response to what is around him. Seeing his intrinsic nature, the practitioner is careful not to give rise to vexations and he knows the environment has no real, permanent existence. Still, he experiences vexations and must use appropriate methods and views, such as meditation and the understanding of causes and conditions, in order to deal with these problems. The methods and views of Ch'an comprise the ox-controlling rope.

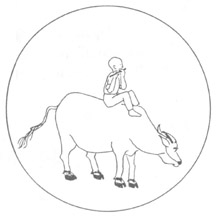

The fifth picture is simply called "Ox Herding." Now a sage, the practitioner easily leads the ox by the rope. He has progressed to somewhere between the eleventh and fortieth stage of Mahayana Bodhisattvahood. Though he has few vexations, he continues to practice diligently and make vows. The direction of the ox herder and the ox is now clear.

"Riding the ox home," the sixth picture, shows an ox well trained and obedient, familiar with the way. The ox herder rides effortlessly on its back, playing a flute. This is the first Bhumi position, or forty-first stage of Bodhisattvahood. The practitioner no longer needs conscious effort to continue to practice and make vows. The ox simply continues forward on the path. The practitioner's actions are appropriate to each situation.

The seventh picture is "Forgetting the Ox." The ox has disappeared. Only the practitioner remains. This point is between the first and the eighth Bhumi stages, and between the forty-first and forty-seventh stage of the Bodhisattva path. The practitioner exerts no effort, and practices spontaneously, unconcerned with goals or purpose. Self cultivation ceases. Beginning practice is like swimming upstream. Great effort is required. Later the swimmer is one with the water. Is there still swimming?

Both the ox and the ox herder have disappeared in the eighth picture. Only a circle, the frame of a picture, remains. The seventh picture removes the ox, which represents the world, the object. Finally, the subject, too, disappears in the eighth picture. Nothing remains. There is no goal and no practitioner.

The ninth picture, "Return to the Origin," shows a mountain and a river. A novice practitioner sees mountains and rivers, but does not recognize them as such. Now the adept sees mountains as mountains, rivers as rivers. He has returned to the world. Everything exists but his attachments. There is no longer practice or no practice, wisdom or vexation. Everything is complete, everyone a Buddha and the environment a Buddha land.

Traditionally, we see a beggar and a ragged, big-bellied monk in the tenth picture. The beggar represents suffering, the monk a practitioner who has completed his practice. He has left the isolation of the mountain and returned to the world to help all beings. He has no vexations, but because others suffer he spontaneously provides help on the path to all needful beings.

I have talked about each ox herding picture, but there is an important point to add. People sometimes adopt a selfish viewpoint from these pictures, because they suggest that we practice until we attain Buddhahood before we even begin to help sentient beings. This is not the way of Buddhism or Ch'an. As soon as the Buddha's teachings begin to benefit you in your life, you must begin to help sentient beings. Even at the very first stage of ox herding, you should help others. Don't simply wait for Buddhahood.

Question: Is this gradual or sudden enlightenment?

Shih-fu: Going through these stages in order is not considered sudden enlightenment. It is best called gradual enlightenment. People who experience sudden enlightenment may share some of these experiences, but not necessarily in this order. The Sixth Patriarch (638-713), who taught before the Pictures were developed, never made reference to such a progression.

The Pictures are useful in representing the process of gradual enlightenment and are studied by practitioners in China and Japan. With faith, we can all seek the ox, Buddha-nature, within ourselves.

T'ien-tai Manuscripts for Meditation

A report on the seminar presented by Professor Dan Stevenson, by Steve Lane and Linda Peer

This September, Professor Dan Stevenson of the University of Kansas presented a two-and-one-half day seminar on t'ien-tai Buddhism as part of the Ch'an Center's Buddhist Studies program. Seminar participants were sent t'ien-tai texts and articles about t'ien tai beforehand, so that they would have a basic understanding of the subject.

Dr. Stevenson began by describing the history of the t'ien-tai school, according to Buddhist scholarship and according to the t'ien-tai school itself. He discussed the great t'ientai master Chih-i's organization and systematization of the sutras which had been translated into Chinese by his time (53 8-597). Chih-i wanted to show that the sutras are not contradictory, as they sometimes seem to be, but rather form a cohesive system which meets the needs and capacities of all sentient beings. Dr. Stevenson began by describing the history of the t'ien-tai school, according to Buddhist scholarship and according to the t'ien-tai school itself. He discussed the great t'ientai master Chih-i's organization and systematization of the sutras which had been translated into Chinese by his time (53 8-597). Chih-i wanted to show that the sutras are not contradictory, as they sometimes seem to be, but rather form a cohesive system which meets the needs and capacities of all sentient beings.

T'ien-tai texts discuss meditation practices in great detail and have been used by many other schools of Buddhism, including Ch'an. On Saturday, Dr. Stevenson talked about these, based on the t'ien-tai text, T'ung Meng Chih Kuan. T'ien-tai emphasizes the development of chih (calming) and kuan (contemplation or observation) simultaneously and equally, and provides methods for practitioners of differing abilities. For practitioners of great capacity there is the "perfect and sudden" method, but for those of lesser capacity there are gradual methods.

The most popular segment of the seminar was the Sunday morning discourse on repentance in Tien-tai, and by extension in all of Mahayana Buddhism. Dr. Stevenson described both the practice of repentance and the manifestations, both good and bad, that can occur as karma is eliminated from the mind stream.

Chan Newsletter Table of Content

|