Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 93, July 1992

Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 93, July 1992

The Reason I'm a Ch'an Monk

Lecture by Master Sheng-yen on May 16, 1992 at Tibet Center

Some of you arc curious about how I became a Ch'an monk. I'm not exactly sure what you would like to know. I haven't really written an autobiography, but I can relate some of the events that led me to where I am now.

The province where I lived in China was once prosperous, but it underwent a slow decline. By the time I was born, the region was impoverished. The land was fertile and rice and wheat could be readily grown, but conditions were such that food was scarce. What I remember most was eating sweet potatoes. They were not of the quality we are used to here. We sliced them and dried them in the sun. Corn, too, was something I remember eating frequently. It was of the quality that was usually fed to pigs.

I was the youngest of eight children. My mother was already 48 years old when I was born. She had no milk to nurse me with, and cow's milk was rare in China at that time. Even female dogs were unable to produce milk to feed their young. Animals were all emaciated. People, too, were malnourished. It was not until I was six that I learned to walk, and it was not until I was nine that I could speak with any facility. I then started school. I completed fourth grade by age 13.

While attending school, I helped my father with his work. It was at this time that a local master was looking for two novice monks to live at his temple. He was in some quandary as to how to find his young novices. He prayed to the Buddha for guidance and it was indicated to him that he should look south of the Yangtze River. The monastery was north of the river, so the master crossed to the side where I lived.

A layman traveling in the vicinity took shelter with us during a rainstorm. It so happened that he was a friend of this master who had told him to keep his eye out for boys he felt might be suitable for

monkhood.

When he saw me, he asked my mother if she was willing to let me leave home. She answered, "If he wants to become a monk, it is up to him. Our family is very poor. I'm afraid that if he stays with us, he won't have enough money to find himself a wife." She added that I had finished the fourth grade, and she did not think that they could afford to let me continue my studies.

The layman turned to me and said, "How would you like to become a monk, young man?" I didn't have the foggiest idea what a monk was or what a monk did. But somehow the idea appealed to me and I said, "Yes, I would like that." The layman wrote my name and birthday in a book and took it to the master.

I soon forgot about this incident, but about six months later the laymen reappeared and said to my mother, "I am going to take your son now. I will take him north of the river to become a monk."

During those last months the master on the north side of the river had taken the date of my birth and put it before the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara and beseeched the image to reveal if I would be suitable for monkhood. He asked three times; three times the answer was "yes." When the layman came to take me to the monastery, I had no strong feeling about going or not going. Nevertheless, I was ready to go. This took my mother by surprise. "Wait a minute," she said, "I thought you were kidding about becoming a monk." But the next day I left with him for the monastery.

When I arrived at the mountain across the river where the temple was located, it seemed that the whole of the mountain was given over to monastery buildings. In the main Buddha Hall I wondered who that big person was, that statue which I soon learned was of the Buddha sitting so serenely within. How could one person be so big?

The size of the main Buddha Hall impressed me. It was so large that it would take at least 20 houses of the size I grew up in to fill it. To look at the Buddha statue you had to bend your head way back. I thought: "the Buddha really is different from ordinary human beings."

I saw another boy just after I arrived who already was a monk. His head was shaved, but differently, not in the usual Buddhist style, but more like a medieval Christian monk with the crown of the head shaved and tufts of hair on the side. I thought that it looked funny, but I liked it anyway. I asked my master if I

could have the same thing done to me. I always hoped to have my head shaved like that, but it never happened. My master thought I was too tall, and that I would look ridiculous tonsured like that.

My master began to introduce me to the other monks. There were so many I could hardly remember their names. The monastic hierarchy was ordered such that each monk had one disciple under him until there were seven "generations." The most recent initiate would be introduced to the monk above him as "Your master," and the monk above him as, "Your grand master," and so on. I found memorizing this genealogy quite onerous.

The master had been expecting two monks. I had arrived, but my counterpart was late. This made me angry. After all, this boy was supposed to be my master, and I was eager to begin training.

He finally arrived, three months later. I asked him, "What took you so long? You're very late." He replied, "Why are you so early?"

He was perhaps one year my elder. I was 13 at the time. It happened that my master, this 14 year old, had a 17 year old brother who died. Of course, Chinese mothers want to have grandchildren, so his mother asked him to return home, marry his brother's widow, and have children. When he left the monastery, my grand master became my immediate master. He said to me, "I always felt that you should be my direct disciple."

What was the training of a young monk like in China at that time? I had two teachers. One taught me sutra recitation and chanting; the other was responsible for teaching me non-Buddhist subjects. What did my master teach me? How to mend and wash clothes, plant vegetables, and cook. A young monk had to rely on himself for almost everything.

When I was 16 I went from the countryside to a branch of my temple in the city of Shanghai. This was a different experience. In Shanghai the monks had to support themselves by performing sutra recitation and chanting for lay people's funerals. Lay people hired us to help their loved ones obtain a favorable rebirth. Chanting and reciting kept us quite busy -- it could go on all night and all day. We might chant in as many as four homes in one day and perform all of the necessary funerary services as well. After doing this for more than a year, I had second thoughts: "Is this all being a monk means?"

One day I saw a copy of the Diamond Sutra and I asked another monk what it was all about. He said, "it talks about emptiness, nothingness -- I'm afraid you might find it a little too deep right now." I asked him when I would be able to understand it. He said, "Practice first, then you may be able to understand it."

Remember, I said that I didn't start school until I was nine years old. As you can imagine, my level of education was pretty low. I had a problem with the recitation of sutras, especially, mantras. My master informed me that my karmic obstructions were heavy, and said that if I wanted to remedy the situation I had better do 500 prostrations to Kuan Yin (Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara) each day.

At first I found this practice exhausting, but after a short while I found that I could do six or seven hundred prostrations in two hours. In three or four months I found that my ability to memorize the sutras as well as my ability to learn in general had vastly improved.

Soon I felt that reciting was not enough. I wanted to understand the sutras, so I found a monastery that offered lectures on the sutras, and I requested my master's permission to attend.

This other monastery required a kind of entrance examination for those who wished to attend the sutra lectures. My master helped me write an autobiography -- that is what I thought they wanted. I even

memorized it. As it turned out, an autobiography was not what they wanted at all -- a completely different topic was required, but they liked my essay, and they thought that my literary skills were very good, so they accepted me anyway.

When I arrived, I met monks from many parts of China. Some spoke with accents so strong that I could hardly understand them at first. Fortunately, the teachers wrote down the important points of the lectures on the blackboard. My memory served me well. I excelled on tests. In the first year I ranked third out of 40, and by the second year I was first. But if you had asked me what I had learned, I would have had to admit that I couldn't really say. I didn't really know what I was talking about, but I knew that my answers were exactly what my teachers were looking for.

I started my practice of meditation at this monastery, but there was really no one to instruct me. The best I could do at first was to memorize sutras and sastras and repeat them in my mind during the time set aside for meditation. When I asked an older monk how to meditate, he simply said, "What? You claim you don't know how to do it, but your approach is very good. You certainly look like you know how to meditate." I didn't feel that way at all. I was pretty naive. I pressed him further: "I've heard that meditation leads to enlightenment. Can you show me how to get enlightened?" What do you think he said to that? Nothing. He just smacked me hard on the side of the head and said, "Here, maybe this will enlighten you. You want to get enlightened in one day? We have been sitting here for decades. What do you think we've been up to?"

From that time on I started to participate in retreats. It seemed to me that everyone else was sitting rather well. Interestingly enough, they thought I was sitting well, too. Some commented, "You will make a good Ch'an master someday." "Why?" I asked. "Because we twitch and move and complain of leg and back pain, but you sit there like a rock, deep in practice," they explained. "That's what you think," I said. "I haven't got the faintest idea of what I'm doing. I just sit and repeat one sutra after the other in my mind. I repeat the Diamond Sutra, then the Surangama Sutra and so forth. That's all I do." They got a good laugh out of that. They said, "It seems that you don't really have it, after all." That's when I first heard about kung-ans (koans) and hua-tou's. My practice began to improve.

When I reached the age of 20, 1 left the mainland and went to Taiwan where I lived for the next eight years. One night, when I was about 28, I was meditating in the monastery where I had been living. I had been sitting all day, and I was at the point where sleep seemed inviting. But I was sitting next to an old monk who continued to meditate despite the lateness of the hour. I asked myself, "Why is this monk still meditating? What keeps him going?" I wanted to sleep, but I was too embarrassed to stop sitting.

My mind was full of questions about the Dharma. I thought this old monk could help me. I tapped him on the shoulder and whispered, "I have questions, lots of questions. Can you help me?" He nodded at me and said, "Ok, ask." I asked him a few questions in succession. He said, "Is that it, or do you have any more questions?" I certainly did. I asked him another. He said, "Is that it, or do you have more?" I continued asking and he continued asking if there were more. This went on for sometime. I thought he was going to listen to all of my questions, and then cut through them all with some marvelous insightful answer. I asked more and more questions. I began to become anxious and agitated.

Finally, the monk hit the mat he was sitting on with a very hard slap and said, "Now put all of this down and go to sleep!" When he did that, all of my questions disappeared, or said in another way, all my questions were resolved. This corresponds to the passage in The Heart Sutra that speaks of emptiness. This was a seminal experience for me.

Many years passed. When I was 46, having lived in the United States for some years, I went back to Taiwan and saw the old monk with whom I shared this experience. He remembered it, too. He asked me what was I doing in the U.S. I told him there wasn't very much to it. All I was doing was teaching meditation. The master said, "Even back then I knew you would be a teacher. But you must have a lineage." He then gave me a Dharma name in his lineage and certified me as his Dharma heir. It was officially written down and signed.

There was another monk there, the master's attendant, who witnessed this interchange. He must have wondered what in the world was going on. Who was this person inheriting the master's lineage? It seemed to happen in a flash.

I prostrated three times to the master, and started to leave when the attendant approached me and said, "So you're living in the U.S. teaching meditation. Will you teach me, too?" I exclaimed, "I don't believe my ears. You're living right here with the master. Why don't you just ask him to teach you how to meditate?" He said, "You don't know what's going on. This master lives in a total state of confusion. He walks around in a fog all day."

One of the lessons of this story is that karmic affinity is important. You may be in the company of a bodhisattva or a buddha, hut without the proper affinity, it could all pass right over your head.

It just so happens that this master is rather well known in Taiwan. He was a second generation Dharma heir of Master Hsu Yun (Empty Cloud), who was perhaps the most famous Chinese monk of the 20th century. Master Hsu Yun had a disciple who transmitted the Dharma to the master in this story. In the Chinese tradition it is rare to be certified in this way. This master had only two disciples who became his Dharma heirs -- another monk and myself.

Question: When you did the prostrations, did the teacher give you anything else to do? Visualization, recitation, or prayer?

The master just told me to prostrate single-mindedly, wholeheartedly. He said nothing else.

Question: Do you recommend using koans? From what you say, it sounds like enlightenment is a flash that completely empties your mind.

Few use koans only. Most people use other methods such as counting the breath. You may try using a koan, but if your mind is too scattered, there is no point. In such cases I often recommend prostrations. Enlightenment does not mean there is nothing in the mind. It means that we cut off our attachments to the world. This includes attachment to oneself. The Heart Sutra states that "form is not other than emptiness; emptiness not other than form; form is precisely emptiness and emptiness precisely form." This is the enlightenment that is attained through practice.

Question: I wonder how to stay centered and calm. I have a number of children. I am always running around. I come here as often as I can. When I am here I am calm, but I easily lose it when I return home. I am always in a hurry.

One very good way to calm your mind in a busy life is to follow the advice given by Shantideva in "The Bodhisattva's Way of Life." Just practice mindfulness; be aware of what the body is doing at all times. As you practice mindfulness, you are aware when your mind becomes unsettled, and you can do something about it immediately. Mindfulness will settle the mind. This practice is common to all forms of Buddhism, but I came to know of it from Shantideva's work.

Question: When you studied koans, were you asked to go off by yourself for a protracted period and then come up with an answer?

When working with the koan, you should be familiar with the story and with the circumstances connected with the story, but you do not contemplate its content. You want to know what the outcome is, but you are not seeking a logical answer. You do not think. Sometimes you use a koan to attain non-discriminating mind.

Question: When we learn meditation, why do we start with counting breaths? Why don't we begin with a more direct method that will focus on the void?

For most of us the mind is simply too scattered. There is no way for the average person to sit down and drop everything. The idea is to use a method to concentrate the mind. Later you can adopt methods that will be focused on what you are describing.

Question: I'm not sure I understood the story where you asked an endless number of questions and your teacher told you to put it all down. Does this mean you were your own teacher? Did you give yourself your own answers about the Dharma and the older monk told you nothing?

You cannot really say that my questions were resolved by me alone or by the monk alone. The resolution was interdependent.

Even though the monk gave me no answers, I would not have been able to resolve these questions had he not said, "Put everything down." And if I had not spent many years in practice, and I did not have a burning desire to resolve these questions, I would not have been ripe at the moment when the master struck the mat. It would have been a different story. So it is hard to say where the resolution came from, me or my master. If you continue asking me questions, perhaps I will do the same with you: slap my pillow and tell you, "put it down and go to sleep."

|

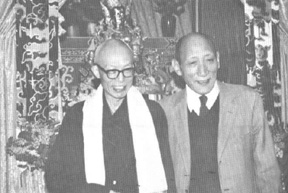

Shifu and Ven. Khyongla Rinpoche at Tibet Center

following Shifu's lecture on May 16, "The Reason I am a Ch'an

Monk." On May 17 Ven. Kyongla Rinpoche spoke at Ch'an Center on

"The levels of Practice in Tibetan Buddhism." This exchange of

lectures was made to foster the spread of the Dharma.

|

Chan Newsletter Table of Content

|