Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 96, March 1993

Ch'an

Newsletter - No. 96, March 1993

Earth Element

Lecture given by Master Sheng-yen on the Surangama Sutra on June 21, 1987

(The preceding lecture can be found in issue No. 97)

Last Sunday I began speaking about the four elements, literally translated as the "four greats." Today we will concentrate on the first element, earth, and the question of its true existence. There are many descriptions and analogies given in this passage from the Surangama Sutra that we are reading today, but they all point to the same thing: the non-existence of the element of earth.

The convention of dividing the world into earth, wind, fire, and water was common in many schools of philosophy and religion in ancient India. Our environment depends on the interdependence and transformation of these elements. All of them coexist at every moment. You cannot have three present and the other missing. It is for this reason that they are called "great": they are indispensable at all times.

Last Sunday, I mentioned the distinction between the internal four elements and the external four elements. As you may remember, when we speak of these four elements, we can talk about them as being inside or outside the body. However, the emphasis in Buddhadharma is on the four elements inside the body, which is a living form. These four elements are essential to the existence of all life forms.

Next the sutra discusses arising and perishing. We may have a simple understanding of these terms: we can understand that a newborn baby is life arising and someone in the act of dying is an example of life perishing. But with a deeper understanding of these terms, we can see that arising and perishing are applicable to both the baby and the one dying.

Ming-yee joked with me at lunchtime today. His birthday happens to be this month, so there was a birthday cake for dessert. Ming-yee said that with each birthday he removes one year from his age. He was just joking, but each birthday could be understood as one year closer to death. And we know that our metabolism functions in every moment of our lives. This involves a continual arising and perishing in every cell of our bodies.

In this view even an infant undergoes arising and perishing. And even a person who is very, very old is in the midst of arising even as he is perishing. There is not as much difference as you might think.

This arising and perishing constantly follow one another. In the I Ching "creation" is expressed in the idea of "arising following arising." Little attention is paid to perishing.

This is, of course, a very hopeful way of looking at things. Nevertheless, arising and perishing always happen together and always follow one another.

This process can be understood in terms of one's thoughts. That is, at any given time there can only be one thought in your mind. When the second thought arises, it means that the previous thought must have perished. Someone involved in a great deal of thinking will have a swirl of thoughts passing through his or her mind, each arising and perishing. Like drops of water cascading over a waterfall, thoughts rush through our minds. But at any one point there is only one thought superseding its predecessor. This pattern is repeated endlessly.

There's another term that I would like to bring to your attention. It describes the smallest possible particle in the element of earth. It is termed, "the mote which is nearest to the void." It signifies a particle so small that if you could somehow manage to cut it down further, what you would be left with would be identical to the void.

I asked Ming-yee how this accords with modem science. He said that according to older theories, matter could be subdivided ad infinitum. But contemporary scientific theories have rejected this infinite partitioning of matter. Indeed, there is much to show that beyond a certain point it is not meaningful to speak of particles.

But I wish to continue with the teachings of the Surangama Sutra. The direction of contemporary science is certainly encouraging, and, who knows, someday theoretical science may advance to the point where it accords with the teaching of the sutra.

The next important term in the sutra, "Tathagatagarbha," is sometimes translated as "Tathagata Store." The word "garbha" has the meaning of store in the sense of holding or keeping. What is stored is a Tathagata, a Buddha. Each one of us has a Tathagata Store. Each one of us holds a Buddha within, but we are unable to see the Buddha that is in our own Tathagata Store.

When you practice to the point where you see into your own nature, the nature which you see into is your Buddha Nature, the Buddha of your Tathagata Store. Is the Tathagata Store here in my chest? No. The Buddha Store is not located in any particular point in your body.

If a human being is without this Tathagata Store, then it means he does not have Buddha Nature. If he has no Buddha Nature, there is no way for him to practice or be able to see Buddha Nature in himself

I just asked someone where her Tathagata Store is? And she said that it was in her consciousness. That's correct. In every single thought of ours the Tathagata Store is present.

There is a saying: every night you embrace the Buddha even when you are deep asleep, and every morning you pay homage to him when you get up. You have sought him for thousands of miles, but he sits right in front of you and you don't recognize him. What does this refer to? The Tathagata Store. We must first believe in the existence of the Tathagata Store before we can have the faith to practice and to attain Buddhahood.

There are two lines right after the words, "Tathagata Store" that are very important, and I would like to discuss them.

The first line says: "The nature of form is true emptiness." "Nature" refers to Buddha Nature or Dharma Nature. All form and phenomena that have manifested from Buddha Nature are, in their true essence, empty. This is the perspective of the Buddha or of one already enlightened.

But there is another saying, "True emptiness is not empty." That is, when we speak of true emptiness, we refer to the fact that nothing stays unchanged and that all things have only a temporary existence. Therefore, it is impossible to truly hold onto or attach to anything, because all things are always in a state of flux. The existence of phenomena is not denied, that would not be genuine Buddhadharma, but our ordinary perception of phenomena is illusory.

It is very easy for people to fool themselves about this point. It often happened in ancient China that people who suffered setbacks in their lives -- a business failure, loss of wealth, unrequited love -- would become discouraged and seek solace in a temple or a monastery. They would begin Dharma practice. Very quickly they would claim that the things that had made them miserable were no longer of any concern to them. But such attitudes were really only feigned. They would say that they had seen the emptiness inherent in all things, but in reality they still mourned their loss. They only wanted to put on a good face for the world to see. This is not true Buddhadharma. It is really sour grapes in a very subtle form.

Someone motivated to practice the Dharma because they have been abandoned by a wife or a

husband, may later encounter their idea of a beauty queen or a knight in shining armor. The Dharma may not seem so important then, and they may feel that the world is not quite as empty as they had thought.

What is the proper understanding of emptiness? To understand emptiness is to look at something, and relate to it as it really is. If a man is married, he must realize that his wife is not simply an object he can put in and take out of his pocket at will. He does not control her. She has her own opinions. She is another sentient being. Both live together and take care of one another. Each one tries to fulfill the responsibilities of marriage. If the man worships her as a Venus-on-earth, then there will be a great deal of attachment to an existence that is not real. On the other hand, if he simply recognizes her as just another sentient being that he happens to live with, and if the couple tries to cooperate with each other, even if the wife decides to leave, the husband will eventually be able to understand and not harbor a grudge. In true emptiness you recognize and accept things as they are. The important thing is that as long as the two stay together, husband and wife have certain responsibilities and obligations that must be fulfilled.

Wealth is the same. If you have money, you should take care of it, and not squander it. But if your fortunes are reversed, you should not become overwrought. After all, wealth is something outside of you. It has nothing to do with who you are. When you can maintain this attitude of non-attachment, that is true emptiness.

Recently, two partners in a business came to see me. They started out as friends, but business quarrels brought them to the point where they were ready to kill each other. Each one complained about the other. As Buddhists, each of them knew that his complaint was an attachment, but what they argued about was so hurtful and hit so close to home, that neither of them could see a way out. How many of you have encountered situations like that?

What can you do? If you become angry enough to grab a knife and run after someone, you may get more vexation than you bargained for. But if it is really the case that setting eyes on someone makes your blood boil, why not simply keep your distance from him?

In this particular situation one person said that he did all the work, the other said that his partner took all the credit. When you reach a point like this, you must realize that you were enemies in a former lifetime, and enemies that meet on a narrow path cannot avoid one another. Now that the quarrel is out in the open, it is best to let it be. If you feel that you have suffered injustice, then consider that you might have owed the other person something in the previous lifetime. Now he's getting something in his turn and you should not be so terribly disturbed by it.

Both of these men still complained to me that the Chinese community was too small -- they would not be able to avoid running into each other. I said, "When you meet, if he says hello, you say hello. If one of you looks unfriendly, that should not prevent the other from smiling. It makes sense that certain incidents will cause you unhappiness, but eventually you can get over them, and it will be like they never happened." Brothers and sisters fight all the time, but it is rare for them to carry childhood grudges into adulthood. They will always know, "This is my sister," or "This is my brother." Dharma practitioners especially should keep this attitude. Feelings of enmity are best recognized, defused, and resolved. There is no profit at all in maintaining them.

Let me now go on to the second line that comes after "Tathagata Store." The line reads, "The nature of emptiness is true form." When you experience emptiness you come to see that all forms, all phenomena have real existence. But it is important to remember that you must not attach to these phenomena, and you must not let them become a source of vexation.

We know that Shakyamuni Buddha attained Buddhahood at the age of 29 or, according to another version, at 34. The Buddha lived until the age of 80, so at the very least he lived here 46 years as the Buddha. What did he do during all those years? He actively taught the Dharma, and it is because of his efforts that Buddhism exists today. If the Buddha had been discouraged and, like the people I spoke of in ancient China, had insincerely and temporarily embraced spiritual pursuits until things in his life improved a little, we would not be practicing as we do today. I wouldn't be here talking to you about the Dharma.

Thus if you really understand this line, "The nature of emptiness is true form," you would know the truth and importance of all phenomena. A person who has achieved this will not lose interest in the world and do nothing. On the contrary, such a person will work hard to fulfill his responsibilities and do whatever he can to help all sentient beings.

The sutra uses the element of earth to illustrate change, the continual arising and perishing of all phenomena. In your understanding of this, you must not fall into extremes. If you simply hold phenomena to be existent, this is wrong because phenomena undergo continual change -- ordinary sentient beings have an incomplete understanding of what is real. Holding that phenomena have no existence is also inaccurate because change itself is a kind of existence, but once again, this is not easily perceived by ordinary sentient beings. Neither existence nor non-existence is strictly correct. Thus, in Buddhadharma our attitude is one of non-attachment to emptiness, non-attachment to existence. In this way we do not get caught up in phenomena, but we do not abandon sentient beings, either. We practice hard and work for the good of all.

Let me return to the story of the two estranged business partners. One of them later asked me, "Shih-fu, how can you prove to me that I really owed my former partner something in a previous lifetime?" I said, "If you do not believe in me, there's nothing I can say. It has nothing to do with my opinion. It is the teaching of the Dharma."

In studying Buddhadharma, faith is very important. We should have faith in the teaching of the Buddha and the method of practice that he taught. This is very useful to us. Developing this faith is perhaps the only way we can approach the future with hope and contentment.

|

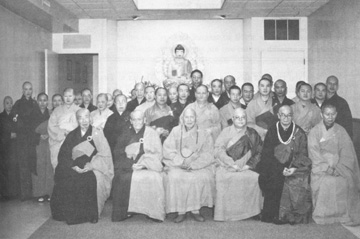

On January 31st, thirty six eminent Chinese monks

and nuns gathered at the Chan Center for a special New year Service.

|

|

Magic show by Bob Lapides during the Chinese new Year

celebration. |

Chan Newsletter Table of Content

|